Wildlife and Conservation 13: Otters

Otters, a childhood book and a beloved film Ring of Bright Water

Welcome to new and existing subscribers. Thank you for reading my article and thereby supporting my writing. You will never know how much I appreciate this.

Introduction:

Video: YouTube, theme song to the film “Ring of Bright Water”, composed by Frank Cordell and sung by the Irish crooner Val Doonican, from Waterford.

I cannot believe that my last Wildlife and Conservation article was published on 18th January. You can find it here, if you would like to read:

Where has the time gone? One minute it was deep, dark winter, when I was beginning to prepare and pack for our journey to Vietnam and Cambodia, whilst assisting with the husbandry of a range of native British mammals and birds at Wildwood Trust Kent, wearing thermal base layers.

My husband’s depression diagnosis; my mother’s unpredicted ten weeks hospitalisation for critical life-threatening illness in Dublin and sixteen flights later, here we are in mid May. With the sweet scent of early summer blossom and the first freshly mown grass, I am frantically steam ironing my summer linens before another flight back to Dublin.

Now back to the focus of this article - the beautiful Otter. To whet your appetite, here is a short 2 minute video compilation I created of Loki, the resident otter at Wildwood Trust Kent. He is an absolute darling.

Video: author, I took this footage in February. If you look carefully, you can see Loki precariously scuttling across the thin, crackling ice on top of the pond water, to find his fish

Ring of Bright Water:

I first read this mesmerising book as a young teenager. I still have my original paperback copy. Cats - both domestic and wild - are my ultimate passion in the animal kingdom. However this book and the subsequent film made a huge impression on me as a youngster, so much so that Otters are my second favourite wild animal.

In 1957, after travelling in southern Iraq, Gavin Maxwell (1914 -1969), a Scottish naturalist and travel writer, returned to the West Highlands of Scotland with an otter cub called Mijbil (Mij for short).

Photo: Gavin Maxwell

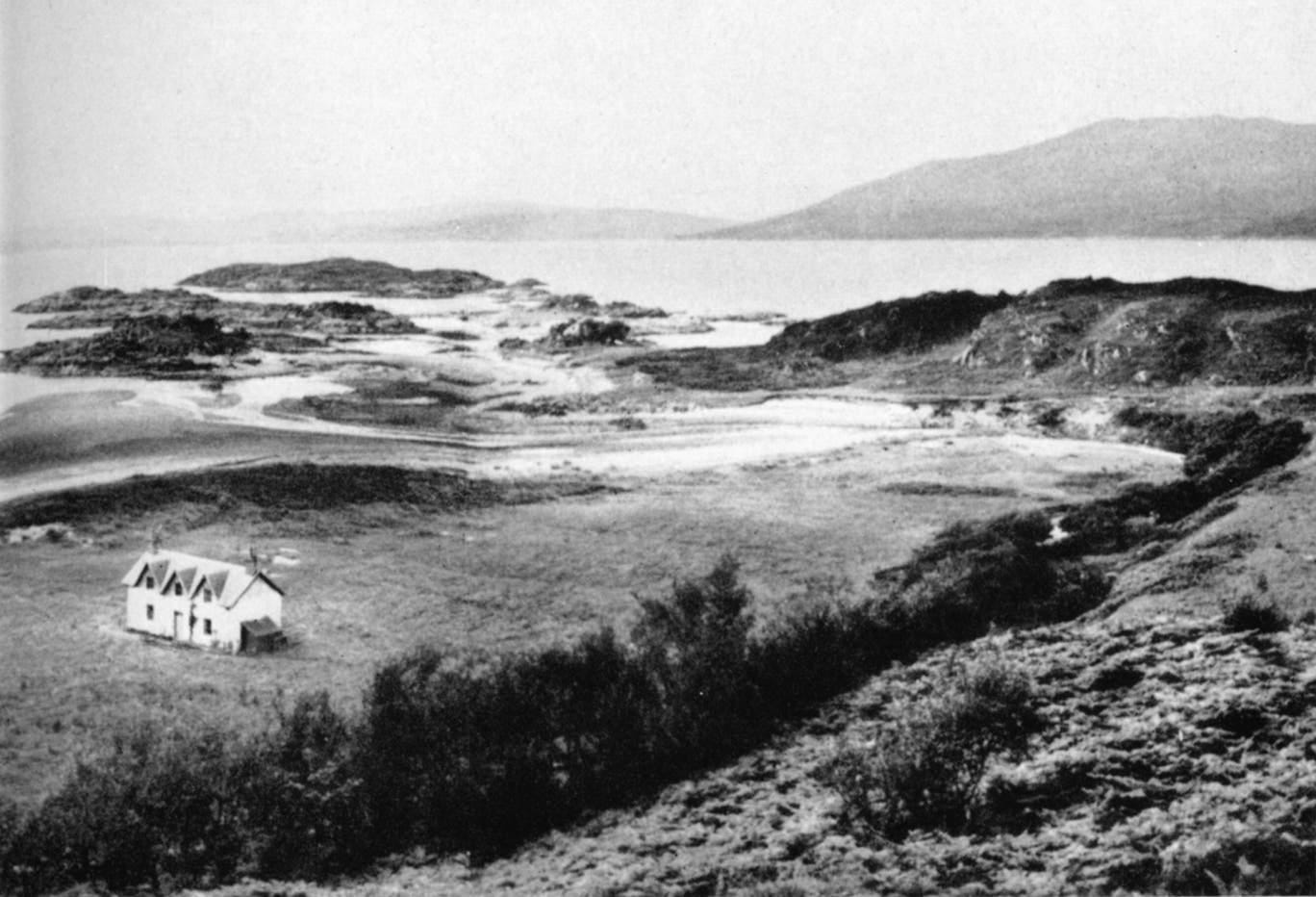

Written in a remote abandoned cottage, on a shingle beach beside the sea, this enduring story evokes the unspoilt seascape and wildlife of a place Gavin Maxwell called Camusfearna.

Photo: Robin McEwen, Camusfearna, Ring of Bright Water

Ring of Bright Water chronicles Gavin Maxwell's first ten years with the Iraqi and West African otters Mij, Edal and Teko, and touched the hearts of readers the world over, bringing to life his experience with these playful animals in this natural paradise.

Photo: Gavin Maxwell, Mij

The title of Gavin Maxwell’s book took its name from the poem The Marriage of Psyche written in 1952 by Kathleen Raine, who was in love with Gavin Maxwell.

He has married me with a ring, a ring of bright water

Whose ripples travel from the heart of the sea,

He has married me with a ring of light, the glitter

Broadcast on the swift river.

He has married me with the sun’s circle

Too dazzling to see, traced in summer sky.

He has crowned me with the wreath of white cloud

That gathers on the snowy summit of the mountain,

Ringed me round with the world-circling wind,

Bound me to the whirlwind’s centre.

He has married me with the orbit of the moon

And with the boundless circle of stars,

With the orbits that measure years, months, days, and nights,

Set the tides flowing,

Command the winds to travel or be at rest.At the ring’s centre,

Spirit, or angel troubling the pool,

Causality not in nature,

Finger’s touch that summons at a point, a moment

Stars and planets, life and light

Or gathers cloud about an apex of cold,

Transcendent touch of love summons my world into being.

Ring of Bright Water received rave reviews and became a masterpiece when it was first published in 1960 and sold over two million copies worldwide.

The book was later adapted into the successful 1969 film, Ring of Bright Water, starring Bill Travers and Virginia McKenna, who also both starred in the film Born Free.

Video: YouTube, trailer for 1969 film “Ring of Bright Water”

The film held its premiere in aid of the World Wildlife Fund on 2 April 1969 at the Odeon Leicester Square, London, attended by the late Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh.

I have including a YouTube link for the full feature, just in case you would like to watch it. It is a beautiful film that will bring a tear to your eye. And the theme music is gorgeous. They really don’t make films like this anymore:

Video: YouTube, Ring of Bright Water, full film, 1 hour 44 min. A wonderful family film to watch with your children or grandchildren

The Otter Lutrinae :

Lutrinae is a subfamily of the Mustelidae family, which includes badgers, martens, polecats, weasels, ferrets, wolverines and mink.

Otters are aquatic, semi-aquatic or marine, living in rivers, fresh water lakes or around coastal sea water. They have sleek, streamlined powerful bodies for swimming, waterproof fur and usually webbed feet.

Otters have unique valves in their nostrils and ears, which close to stop water entering. Their special eye lenses do not experience distortion in water, giving them clear underwater vision.

Otters can feel the movements of fish using their distinctive whiskers called vibrissae, enabling them to hunt in dark, muddy waters. Other mammal species such as cats also have vibrissae.

As a reminder, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) classifies species into one of nine Red List Categories: Extinct, Extinct in the Wild, Critically Endangered, Endangered, Vulnerable, Near Threatened, Least Concern, Data Deficient and Not Evaluated.

Vulnerable, Endangered and Critically Endangered species are considered to be threatened with extinction.

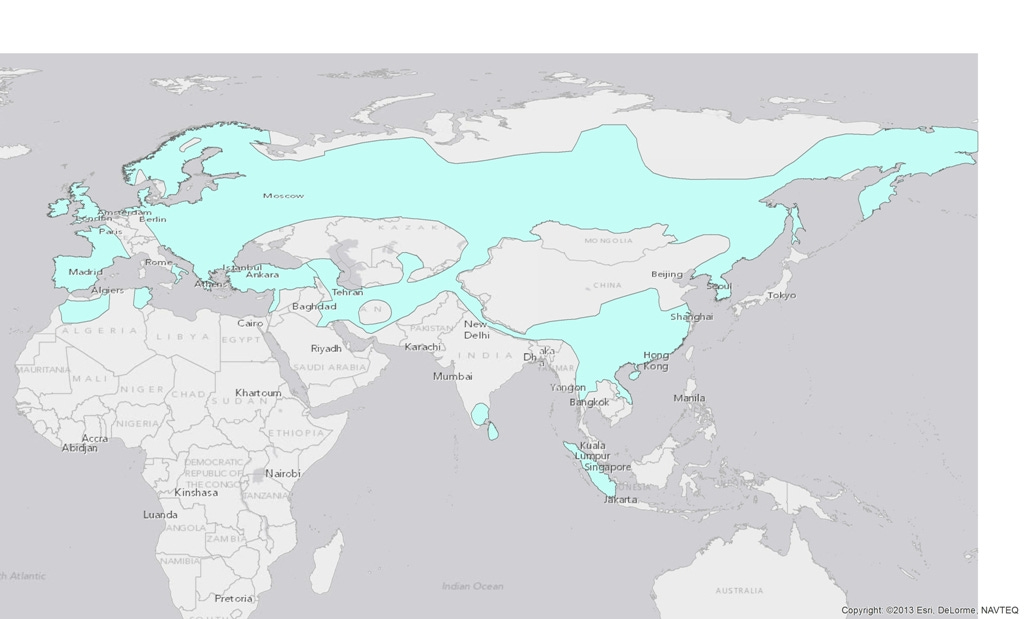

The main threats to otter populations are persecution, habitat loss, environmental pollution, global warming, road accidents and the illegal pet trade, especially in Indonesia and Japan (IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 36(1) 2019).

Image: Otter Specialist Group, The Illegal Otter Trade in South East Asia, Traffic Report, June 2018

The Otter subfamily can be subdivided into 14 species:

Image: Otter Specialist Group

Eurasian otter (Lutra lutra):

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Near Threatened (2020)

Photo: author, Loki, Eurasian Otter, Wildwood Trust Kent

Loki, the playful and mischievous otter that I have worked with at Wildwood Trust Kent, is an Eurasian otter. The Eurasian Otter is one of Britain’s largest remaining carnivores. Eurasian Otters live in a wide range of aquatic habitats, including large rivers, lakes and ponds, moorland streams, estuaries and sea coasts.

Photo: author

Typical Eurasian otter size varies between 102 - 138 cm (body 57 - 70 cm; tail 35 - 40 cm) and weight ranges between 4 - 11 kg. Its powerful long, thick tail helps the otter to twist, turn, steer and dive.

Photo: author

The otter’s fur is waterproof, consisting of two layers. The inner layer is soft and fluffy, providing heat insulation. In between these short inner hairs grow much longer, oily guard hairs which provide the otter with waterproofing.

Photo: author

The Eurasian Otter can swim up to 12 kilometres per hour in water. On land, the otter can surprisingly reach a speed of 20 kilometres per hour.

Eurasian Otters can dive up to 14 metres deep and hold their breath for up to 4 minutes if necessary. They have a transparent nictitating membrane (a third eyelid) which enables the Eurasian Otter to see when hunting under water.

Eurasian Otters feed mainly on fish, which makes up 70 – 95% of their diet. They also eat shellfish, eels, newts, frogs, birds, eggs, small mammals and even aquatic insects and worms. At Wildwood Trust Kent, Loki is partial to mice and occasional beef mince, in addition to his daily fish.

The Eurasian otter is solitary and is usually nocturnal but can be diurnal. It is territorial and will mark its territory by depositing faeces (spraints) in prominent places within it. Males have wider territories than females. The male’s territory may overlap with several females, mating with all of them.

With respect to breeding, typically 2 - 4 cubs are born in spring, in a den known as a holt. In the wild, pups would live with their mother for the first year. The pups usually do not swim in water for the first 2 to 3 months of their lives.

A Eurasian otter’s lifespan can reach 14 years in captivity, but in the wild, it can live an average of 5 years. Loki, the resident Eurasian Otter at Wildwood Trust Kent, will be 9 years old in June this year.

Predators include birds of prey, crocodiles and dogs. The main threats to the Eurasian otter are pollution, poaching, habitat loss, accidental trapping and road kill.

The Eurasian Otter has the widest distribution of any of the 14 different otter species. Its population is declining in many countries in which it is not protected and in others its status is unknown.

By the 1960s, their range in Britain had reduced to mainly Scotland and western Wales. Pollution from chemicals leaching into water courses was attributed to one of the major causes of this significant 20th century decline.

Following a ban on harmful pesticides across Europe in 1979, Eurasian Otter numbers have made a spectacular comeback in Ireland and Britain.

Hairy-nosed Otter (Lutra Sumatrana):

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Endangered (2020)

Photo: Otter Specialist Group

The Hairy-Nosed Otter is recognisable by its hairy nose pad and white upper lip.

Its size varies between 105 -113 cm (body 50 - 82 cm; tail 35 - 50 cm) and its weight ranges between 5 - 8 kg.

The Hairy-Nosed Otter’s diet consists of fish, water snakes, frogs, lizards, terrapins, crustaceans and insects that live in swamps and shallow coastal waters.

The IUCN states that this otter’s predators are unknown. Main threats to the Hairy-Nosed Otter are poaching, habitat loss, accidental trapping, road kill, overfishing, the illegal pet trade and pollution.

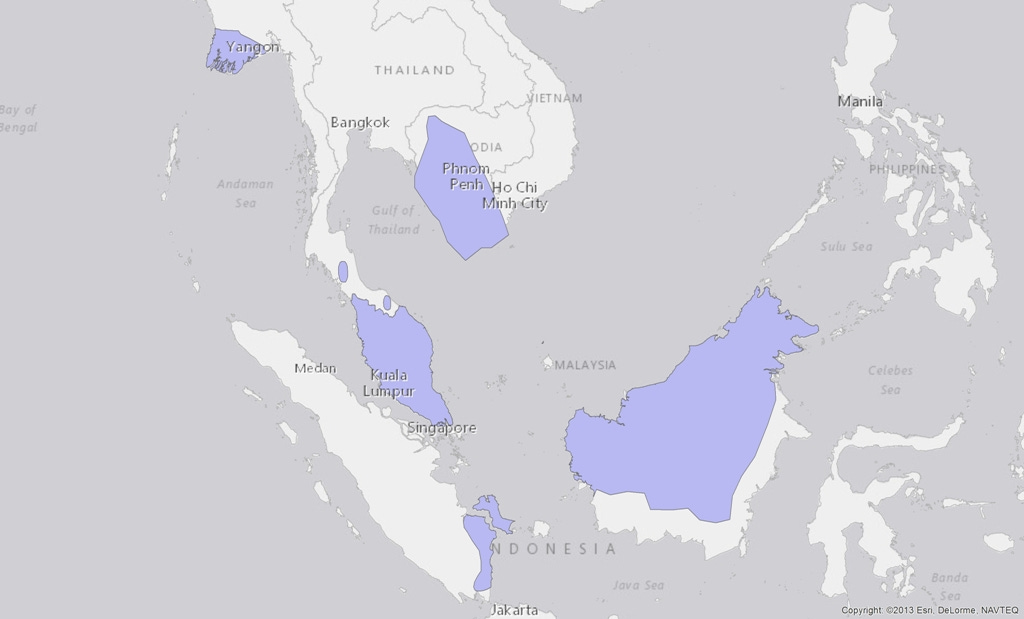

The Hairy-Nosed Otter originally ranged from Myanmar to Việt Nam and also to Sumatra Island, but its range is estimated to be shrinking in each country. The IUCN Red List Fact Sheet for the the Hairy-Nosed Otter states:

The species is suspected to have declined by at least 50% or more in the past three generations (30 years based on Pacifici et al. 2013) due to habitat destruction and degradation, pollution, bycatch and prey depletion due to over fishing and illegal hunting. It is anticipated that the current rate of decline will continue into the future and further threaten this species. The most important habitat is assumed to be peat-swamp forests in Thailand, Việt Nam, Malaysia, Indonesia and in flooded forests in Cambodia. They are observed in mangrove and tropical forest. These habitats have been destroyed for development in large scale. In its entire range, the Hairy-nosed Otter is under increasing pressure due to extensive poaching. In Cambodia, around the Tonlé Sap Lake and other places, poaching of otters and other wildlife is common. In Việt Nam, otters are hunted for illegal wildlife trade, for meat and medicinal use. Wildlife trade involving Lutra sumatrana as pets was recorded several times in Indonesia. In Borneo, the destruction of forests for palm oil plantations, and soon, the anticipated transfer of the capital of Indonesia to Kalimantan does not augur well for the future of this species. The principal threat to the fauna of the Southeast Asia is the burgeoning human population and resultant pressure of this growth on natural resources. Lack of adequate prey species and suitable undisturbed habitat are putting additional pressures on all wildlife species, including the Hairy-nosed Otter. A combination of all these factors may lead to the extinction of the species unless appropriate conservation measures are taken soon.

The Hairy-Nosed otter is considered a miracle: It was actually declared extinct in 1998. However, this petite, shy otter was recently and with excitement rediscovered in Việt Nam, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, Borneo and Cambodia, mostly due to camera trap evidence.

Nevertheless, the Hairy-Nosed Otter is so endangered and the risks to its survival so high that ex-situ conservation methods involving capturing individuals for reproduction in captivity are being considered to improve the chance of a future restocking of nature reserves.

Smooth-coated Otter (Lutrogale perspicillata):

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Vulnerable (2020)

Photo: Otter Specialist Group

Mijbil, the otter in Gavin Maxwell’s Ring of Bright Water was a Smooth-Coated Otter. In fact, when Gavin Maxwell brought Mij to the London Zoological Society (LZS), Mij was formally identified as a new subspecies of the Smooth-Haired Otter called Lutrogale perspicillata maxwelli.

Wilfred Thesiger, the British military officer, explorer, writer and photographer wrote in The Marsh Arabs (1964) that Gavin Maxwell accompanied him, travelling in his tarada around Iraq for seven weeks in 1956. It was Thesiger who obtained the six week old Mij in Basra, as Maxwell had always wanted an otter as a pet.

A Smooth-Coated Otter has a typical size of 106 - 130 cm (body 65 - 79 cm; tail 40 - 50 cm) and its weight ranges between 7 - 10 kg.

Smooth-Coated Otters form large, vocal family groups, hunting together on fish, shrimps, frogs, crabs, insects and birds.

They are typically found in the slow flowing waters associated with rice paddies and floodplains. Smooth-Coated Otters may use large rivers in some regions. They need thick riverside vegetation in which to hide, dig dens and raise cubs.

In the short BBC clip below, you can see a large, social group of Smooth-Coated Otters thriving in ultra urban Singapore, thanks to a national ten year waterways cleanup project during the 1970s and 1980s and legislation that prohibits the hunting, killing, capturing and selling of any wild animal.

Video: BBC Earth, 1 minute 42 sec

The Smooth-Coated Otter’s predators are large carnivores and crocodiles.

Threats include poaching for its fur (a short, smooth, velvety fur, warm chocolate brown on the back and soft grey on the stomach), habitat loss, accidental trapping, the illegal pet trade and pollution.

A close cousin to the Small-Clawed Otter, the nocturnal Smooth-Coated otter has a large distribution that is slowly shrinking, a fact made startlingly clear by the remnant of a population in Iraq (see map above) - its range once spread from the Middle-East to southeast Asia.

Marine Otter (Lontra felina):

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Endangered (2022)

Photo: Otter Specialist Group

The Marine Otter is smallest of the new world species and is the only exclusively marine species apart from the sea otter. It lives on rocky coasts, using caves for shelter and dens. The Marine Otter never strays further than 30 m inland.

Its length varies between 87 - 115 cm (body 57 - 79 cm; tail 30 - 36 cm) and weight ranges between 3 - 6 kg.

The Marine Otter’s diet includes crustaceans, octopus and molluscs and some slower moving fish.

It is monogamous, mating for life.

Predators include birds of prey, orcas and sharks. The main threats to the Marine Otter are poaching, habitat loss, accidental trapping and persecution.

The Marine Otter is found on the Pacific coast in South America. Its habitat is very fragmented and the areas in which this otter no longer occurs increase every year.

Southern River Otter (Lontra provocax):

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Endangered (2019)

Photo: Otter Specialist Group

The rare, shy Southern River Otter lives in freshwater river and lake systems with abundant riparian vegetation, close to the rocky coastal habitats of Argentina and Chile.

The Southern River Otter’s size varies between 100 - 116 cm (body 57 - 70 cm; tail 35 - 46 cm) and its weight ranges between 5 - 10 kg.

Its diet includes fish, crabs, molluscs and birds.

Predators include free-ranging dogs and birds of prey. The main threats are habitat loss, exploitation, fishing conflicts, poaching and invasive fish species such as imported salmon that eat local fish species and are too fast swimmers for the Southern River Otter to hunt.

The Southern River Otter has been wiped out of much of its Argentinian area because of habitat loss and poaching for otter pelts.

Neotropical River Otter (Lontra Longicaudis):

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Near Threatened (2020)

Photo: Otter Specialist Group

The Neotropical River Otter is large with a very long tail (hence the Latin name). This otter has a large distribution in Central and South America but an unknown population size.

The semi-aquatic Neotropical River Otter exists in a wide range of habitats including rivers, streams, lagoons, ponds and in coastal areas close to fresh water. It has even been observed 3885 m above sea level in Chile.

Its size varies between 90 - 136 cm (body 50 - 79 cm; tail 37 - 57 cm) and weight ranges between 10 - 14 kg. Note those tail dimensions.

Its diet consists of fish, crustaceans, smaller mammals, birds, reptiles and insects.

Predators include caimans, anacondas and jaguars. The main threats to the Neotropical River Otter are habitat loss, pollution, mining and poaching.

Local fishermen have been known to train the Neotropical River Otter to help them corral fish into nets, just like sheepdogs!

Between the 1950s and the 1970s, a very high hunting rate nearly drove this mustelid into extinction when over 30,000 otters were killed every year for their pelts. Now, they are protected in every country in which they occur.

In March 2024, a fourteenth species of otter was identified as Lontra annectens, using genome-wide nuclear markers. Previously, this species was thought to be one of three subspecies of the Neotropical River Otter (Lontra Longicaudis).

North American River Otter (Lontra canadensis):

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Least Concern

Photo: Otter Specialist Group

The North American River Otter is another success story. Pollution and trapping had almost wiped out this otter by the 1950s. Fortunately, campaigning and legislation resulted in cleaner waters; trapping management and reintroduction in states where they had had practically become extinct. Today, this otter is thriving in Northern America.

This otter is active, playful and sociable - living in small groups consisting of a mother plus offspring.

The North American River Otter’s size varies between 100 - 153 cm (body 66 - 107 cm; tail 31 - 46 cm) and its weight ranges between 8 - 11 kg.

This otter’s habitat includes all freshwater systems, estuaries and some coastal and marine areas depending on the availability of adequate prey and riparian cover.

The North American River Otter eats mainly fish, molluscs and crustaceans.

Predators include big cats, alligators, coyotes, dogs and wolves. Main threats are pollution, poaching, habitat loss, accidental trapping and road kill.

Congo Clawless Otter (Aonyx congicus):

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Near Threatened (2020)

Photo: Otter Specialist Group

Its reduced whiskers, lack of webbing, tiny claws and dental morphology, together with observations, indicate that this African otter species is typically terrestrial, exploring marshes and forests.

The Congo Clawless Otter’s head and neck is frosted with a brilliant white, that make its characteristic black markings under the eyes even more evident, almost Batman like.

This otter uses its fingers to search for molluscs, crabs, earthworms and frogs from the muddy banks.

The Congo Clawless Otter’s size varies between 110 - 150 cm (body 79 - 95 cm; tail 50 - 56 cm) and its weight ranges between 12 - 17 kg.

Predators include large carnivores, crocodiles and dogs. Its main threats are poaching, habitat loss, hunting, overfishing and the illegal pet trade.

The Congo Clawless Otter is the least studied of the African otter species. We do know that this otter is typically solitary.

This otter is found in the Congo region, West Africa.

The Congo Clawless Otter has been protected by the remoteness of the Congo forest and the difficulty of catching it. However, firearms are growing in prevalence in the region, providing a possible 10-fold increase in hunters’ success rate over traditional practices. Road-building, opening up the forest for timber exploitation and construction of large hydroelectric projects could also reduce the protection afforded to date.

African Clawless Otter (Aonyx capensis):

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Near Threatened (2020)

Photo: The Otter Specialist Group

The African Clawless Otter is adaptable and can be found in towns, cities, highly polluted rivers, natural freshwater and marine habitats, provided that there is freshwater available to wash off the salt.

This otter is dexterous due to its lack of claws and reduced webbing. This plus its large molars enable it to crush crabs and lobsters, although it enjoys eating frogs, fish and insects too.

The African Clawless Otter is typically solitary, however if prey is plentiful, it can be found in family groups.

Its size varies between 115 - 160 cm (body 72 - 95 cm; tail 40 - 60 cm) and its weight ranges between 12 - 19 kg.

Predators include big cats and crocodiles. Main threats are poaching, habitat loss and hunting.

Asian Small-clawed Otter (Aonyx cinereus):

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Vulnerable (2020)

Photo: Otter Specialist Group

Similar to the African Clawless Otter, the Asian Small-Clawed Otter is very dexterous due to its reduced claws and webbing.

They form lifelong monogamous pairs and form playful, social groups, sometimes with up to twenty otters.

Its size varies between 65 - 94 cm (body 40 - 63 cm; tail 25 - 35 cm) and its weight ranges between 2 - 5 kg.

The Asian Small-Clawed Otter is adaptable with respect to habitat - living in fast flowing waters in Thailand, pools of stagnant water in West Java, swamps, rice paddies, peat and mangrove forests.

They eat crabs, snails, molluscs, insects and small fish.

Predators include large carnivores and crocodiles. Main threats are poaching, habitat loss, overfishing, the illegal pet trade and pollution.

Sadly, there is a lack of legislation in Cambodia and Indonesia to protect both the Asian Small-Clawed Otter and the Smooth-Coated Otter.

Sea Otter (Enhydra lutris):

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Endangered (2020)

Photo: Otter Specialist Group

Unlike other marine mammals, the Sea Otter has no blubber to protect it from hypothermia. Instead, it has the thickest, densest fur of all mammals: 500,000 hairs per square centimetre. It was this feature that made its fur so desirable and nearly caused this otter’s extinction.

Its size varies between 67 - 163 cm (body 55 - 130 cm tail 12 - 33 cm) and its weight ranges between 23 - 36 kg.

Sea Otters are social mammals and live in single sex groups, in contrast to other otter species. They rarely come ashore but float instead, diving for clams, crabs and urchins.

Sea Otters are found off the coast of Japan, the Kamchatka Peninsula, Russia, the North West Pacific, Alaska, Canada, Washington State, Oregon, California and Mexico.

Predators include orcas, white sharks, eagles and bears. Despite making a remarkable recovery in Alaska and the Northeast Pacific, Sea Otters are still in danger from predators, poachers and water-borne toxins which are increasing due to warmer water temperatures.

The main threats for the Sea Otter are pollution, poaching, accidental trapping and oil spills.

Giant Otter (Pteronura Brasiliensis):

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Endangered (2020)

Photo: Otter Specialist Group

The Giant Otter from South America is the largest otter species in the world.

Its size varies between 145 - 180 cm (body 96 - 123 cm; tail 45 - 65 cm) and its weight ranges between 24 - 34 kg.

Its latin name, Pteronura, refers to its flat, winglike (ptero) tail (nura), which is one of the Giant Otter’s unique features, in addition to the markings on its neck that are used to identify individuals.

The Giant Otter is monogamous and territorial. With its life mate, it leads a large, diurnal, vocal, social family group that sleep, play and hunt together.

The Giant Otter’s freshwater habitat includes large rivers, streams, lakes and swamps.

Its diet is predominantly fish, but can also include caiman and other vertebrates. The Giant Otter is an opportunistic hunter.

Historically, hunting for the pelt trade was the greatest threat to the Giant Otter. It came close to extinction in the early 1970s in Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela, Bolivia, and Brazilian Pantanal. From 1960 to 1969, records indicated a regional harvest of 12,390 giant otter skins. In 1973, giant otters were placed on CITES Appendix I and the enforcement of international trade restrictions on Giant Otter skins in 1975 finally ended Giant Otter hunting.

The Giant Otter’s predators include big cats and caimans. Today, main threats are pollution, poaching, habitat loss and persecution.

Spotted-Neck Otter (Hydrictis maculicollis):

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Near Threatened (2020)

Photo: Otter Specialist Group

The Spotted-Neck Otter can be identified by unique white patches on its upper lips and/or neck.

In contrast to the other two African otter species, the Spotted-Neck Otter is slim, has webbed paws, reduced whiskers and is diurnal in some areas.

Its size varies between 95 - 115 cm (body 57 - 69 cm; tail 33 - 44 cm) and its weight ranges between 4 - 7 kg.

The Spotted-Neck Otter’s habitat includes freshwater lakes and rivers.

It eats a diet of fish, frogs, crabs and small water birds.

If there is sufficient prey, the Spotted-Neck Otter will form social groups of all males or juveniles or two mothers with cubs.

Its predators are large carnivores, crocodiles, dogs and fish eagles. Main threats are persecution, poaching, hunting, habitat loss, accidental trapping, overfishing and invasive fish species such as the Nile perch.

Reflections:

According to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), about half of all otter species are threatened. The IUCN lists five species: the Giant Otter, the Marine Otter and Southern River Otter of South America; the Sea Otter of North America; and the Hairy-Nosed Otter of Asia as endangered and two species: the Asian Short-Clawed Otter and the Smooth-Coated Otter as vulnerable.

But there has been progress with time:

Can you believe it. We have been working with otters for 50 years! In 1974, all thirteen (now fourteen!) otter species were critically endangered, most close to extinction. How was this dire situation reversed, locally and globally? Is there one action or agreement that paved the way to recovery? I'll give you a hint. Placing all otter species on CITES Appendix I or II in 1978 was a good start, but assessing each species and developing conservation measures took many decades more.

Looking ahead, will threats, like climate change and habitat destruction, destroy our hard work and eradicate otters from our planet? Do we have the means to secure their future? This congress will provide some answers. I strongly believe that: Yes, we can and here's how we can do it.

Nicole Duplaix, Opening Statement, IUCN SSC OSG 16th International Otter Congress "Transforming Research Into Policy - United at Crossroads", 24th-28th February 2025, Lima, Peru.

If you are really interested and want to find out more about the strategies the IUCN and the affiliated Otter Specialist Group are implementing, I have provided the link to the abstracts for every presentation at the conference.

A private person, sadly Gavin Maxwell experienced a troubled, short-lived life. As a homosexual living in a conservative postwar Britain, he understandably did not publicly share his sexuality.

A writer and a poet, her love unrequited, Kathleen Raine's relationship with Gavin Maxwell deteriorated after 1956, when she indirectly caused the death of Mijbil.

Maxwell was briefly married to Lavinia Renton (daughter of Sir Alan Lascelles and granddaughter of Viscount Chelmsford, Wilfred Thesiger’s uncle) on 1 February 1962. The marriage lasted approximately one year and they divorced in 1964.

Kathleen Raine held herself responsible not only for losing Mijbil but for a curse she had uttered shortly beforehand, frustrated by Maxwell's homosexuality: “Let Gavin suffer in this place as I am suffering now.”She blamed herself subsequently for Maxwell's misfortunes, beginning with Mijbil's death and ending with the lung cancer that tragically killed him aged 55 on 7 September 1969.

In my next article, I return to France and to the farmhouse hotel where we celebrated our wedding with family and friends, when we remarried in 2009. I visit the fromagerie originally set up at the back of the farmhouse hotel, where les Frères Bernard started making their own cheese, Sablé de Wissant, over thirty years ago. Today, the brothers make 9 varieties of cheese, using milk from two local farms, and export their award winning cheeses as far afield as Japan and Australia.

Thank You for reading Free-Styling @60.

Clicking the heart, sharing and/or commenting below all help other people find my work.

If you have enjoyed my writing and aren’t already a subscriber, please do sign up here - it’s free.

I remember reading and seeing "Ring of Bright Water," but, unlike "Born Free," I hadn't thought about it in decades.

How did the woman "indirectly" cause the death of Mijbil? I wondered about that.

I also enjoyed looking at the species of otters -- some's faces are very different!

Beautifully written article,very informative

So good I read it twice

The otter is a truly remarkable creature

Very well done to the author