Sourdough Bread Making Master Class

Ursa Minor Bakery, Ballycastle, County Antrim, Northern Ireland

Introduction:

In my mind, I have a dream. I do have to confess it is my personal dream - my husband and I are still debating whether it will be our shared dream.

I imagine, say five years from now, that we have finally returned home to Ireland - and we set up a tiny weekend market stall together - me selling my freshly made, tangy chèvre cru cheese crottins and my husband selling his home-made real soda bread and sourdough. Minimal, low key, on a table just a little bit bigger than the size of an old school desk. But offering sustainable, home-made high quality real bread and cheese for our local community, on a small scale. I picture something like this:

Photo: Kris St, Pinterest

Photo: Mae Mu, Unsplash

My husband was a young baker when I met him first in 1988, having left school prematurely at 14 and trained as an apprentice baker with Johnson, Mooney & O’Brien bakery in Dublin. Long, blonde hair down to his shoulders; strong, flour covered hands as big as a bear’s paws; sparkly blue, laughter-filled eyes and a rich, inner Dublin city accent that he has never lost. Reader, I fell in love.

Mr C retrained and is now a silver fox, well seasoned, family lawyer, viewing retirement slowly approaching on the horizon in the next 5 or so years. Not without trepidation. Mr C would probably tell you himself, he is not a fan of change.

So, for his Christmas present, I gave my husband the gift of a Sourdough Master Class with Dara Ohartghaile at Ursa Minor bakery in Ballycastle, County Antrim, Northern Ireland.

My husband generously gifted me the Ranger Day experience at the Big Cat Sanctuary, that I wrote about previously last month:

Such are our diverse interests. However, we will be travelling to Vietnam and Cambodia in a week’s time and my husband’s company were unable to give him additional leave for this surprise Christmas gift, so close to our Asian adventure.

This is how I came to be doing the Sourdough Bread Making Masterclass at Ursa Minor Bakery last Saturday. As I said to Dara and my fellow student bakers during group introductions, I love food, I enjoy cooking and I can make a good soda bread that I’m proud of - but I’m pants at baking cakes, pastry and yeast leavened bread.

So here I am and what a wonderful, worthwhile experience it was. And I got to meet up with my sister and nephew, collecting them in Belfast from the Dublin train.

Image: https://www.theirishroadtrip.com/the-causeway-costal-route/

We were lucky enough to enjoy the glorious Causeway coast and the ancient Glens of Antrim countryside during some exceptionally dry, sunny yet cold February weather in Ballycastle, North Antrim, our father’s birthplace and final resting place.

Photo: author, Dark Hedges, near Ballycastle

Photo: author, Fair Head

Real Bread:

Did you know that February is Real Bread awareness month?

So what is real bread? The Real Bread Campaign’s definition is:

Real Bread is made without chemical raising agents, so-called processing aids or any other additives.

Real bread is made simply by combining these four ingredients:

Flour – Water – Yeast – Salt

Genuine sourdough bread is Real Bread leavened using only a live sourdough starter culture - no additional or alternative raising agents, such as baker's yeast.

in his most recent articlesays of wheat production and sourdough bakery in Ireland:

As I have already observed, before the Normans, the native Irish primarily baked barley and oat breads, often as flatbreads cooked on griddles or baked in ashes. Of course, monasteries and Viking towns had changed that introducing clay oven, but wheat was a till luxury, used mainly by the elite and monasteries. The Normans expanded wheat cultivation, making wheat bread more widely available, especially in towns. Oven-baked wheat loaves became more common in Norman-controlled areas, replacing some traditional griddle-baked oat cakes. New baking techniques were introduced, including sourdough-style leavening and enriched doughs.

Ursa Minor Bakery:

Ciara & Dara Ohartghaile, both native to the north Antrim Causeway coast, were travelling and working in New Zealand and became impressed with the quality and taste of the sourdough bread and brewed coffee one could find in cafés throughout New Zealand.

Photo: Ursa Minor Bakery, Ciara and Dara on Croagh Patrick summit, County Mayo, Clew Bay in the background

Whilst local people in Northern Ireland have a long tradition of baked breads and cakes and a sweet tooth, at the time, most bread, cakes and pastries produced in Northern Ireland were mass produced in factories.

At the Sourdough Bread making Masterclass, Dara shared that eleven years ago, on 22/02/14, having returned home to Ireland from New Zealand, Dara and Ciara set up their own start - up sourdough bakery, initially in farmers market pop-ups, baking their first loaves in Dara’s mother’s oven because her oven was hotter than their own. Their first wholesale order for sourdough bread was for the Lost and Found café in Coleraine (now in Portstewart).

Ciara and Dara initially began the Ursa Minor bakery and café in the courtyard, beside Ballycastle Garden Centre, up the hill on Castle Street.

Photo: Ursa Minor Bakery, on Castle Street in the early days

Both Dara and Ciara are self-taught bakers and their motto is “slow, honest food”. Their best-selling sourdough loaf is made with just three ingredients: flour, water and salt.

All their bread is sourdough, meaning it is naturally leavened and free from commercial yeast. Ursa Minor is part of the Real Bread network and pride themselves on making bread free from additives and preservatives.

As well as offering their baked goods to the public, Ciara and Dara continue to provide wholesale sourdough bread and pastries to quality cafés and restaurants on the north coast, including Lost and Found; Harry’s Shack restaurant (Portstewart); Lir Seafood restaurant (Coleraine); Barn Door Coffee & Kitchen (Coleraine); Broughgammon farm café (outside Ballycastle); Babushka Kitchen café (Portrush) and Chestnutt’s Farm (Portrush).

Continued popularity and demand for Dara and Ciara’s local, sustainable sourdough bread and pastries, enabled them to move into their current Ursa Minor bakery premises on Ann Street, seven years ago.

Here, together with their team, they create a range of gorgeous sourdough breads and pastries. For example, their sourdough croissants are made using 30% stoneground wheat from Manna Heritage Mill in County Monaghan. The dough is slowly fermented over 3 days, resulting in a super flakey texture and a full flavour. Having eaten my fair share of croissants around France in the last thirty years, I can confirm that Ursa Minor croissants are my absolute favourite. Look at these. I wish you could taste them and feel the crunchy, flakey texture in your mouth.

Photo: Ursa Minor Bakery. Sorry I should have taken a photograph of the one I gorged on last Saturday morning, with freshly brewed coffee, but I had scoffed all of it, before I remembered that a photo would have been helpful for this article!

Dara’s sister runs the thriving café on-site, selling delicious, lip-smacking tasty breakfast and lunchtime dishes, using in-season, sustainably grown local ingredients.

Last year in 2024, Ciara and Dara celebrated the tenth anniversary of Ursa Minor Bakery .

Photo: Ursa Minor Bakery

The Ursa Minor Bakery has accumulated a range of awards year on year, including Georgina Campbell’s Best Bakery/café in Ireland; Slow Food awards (founded by Carlo Petrini in Italy in 1986); the World Pastry Awards (laliste1000) and of course the coveted McKenna Guide award, which they have maintained since 2014.

Photo: Ursa Minor Bakery

As a Substack reader, you may already know that Ciara writes here about sustainable food, cooking and baking on the north Antrim coast in her successful Substack called Gorse. And she enjoys regular cold water swimming in that “Baltic” cold sea - brave woman!

Ciara recently celebrated winning the Irish Food Blog Award at the annual Irish Food Writing Awards in Dublin’s RDS in November 2024.

In July 2024, Dara and Ciara set up their own Ursa Minor Bakery School, in Yarn Ballycastle, a brand new multipurpose community creative space, located in the old Northern Bank building, across the road on Ann Street, where they have began to run both bakery and cookery courses, which sell out very quickly.

Dara shared that they have future plans to develop the gardens behind the community hub building, setting up polytunnels to grow seasonal fruit, vegetable and herbs and starting gardening classes for the local community, including children at primary schools. How exciting and forward looking. Catch them when they’re young and it becomes part of their DNA.

One of the team members of the Ursa Minor Bakery team has even set up a pop-up film club in the community hub, in collaboration with the Portrush Film Theatre. The inaugural film shown in the autumn was appropriately The Taste of Things (2023), starring Juliette Binoche.

Image: https://m.imdb.com/title/tt19760052/

Now, that’s right up my street. Ballycastle’s original cinema on Market Street sadly closed in 1980.

Grains used in Flours and Bread Making:

Photo: author, Stone ground, organic strong white flour from Shipton Mill

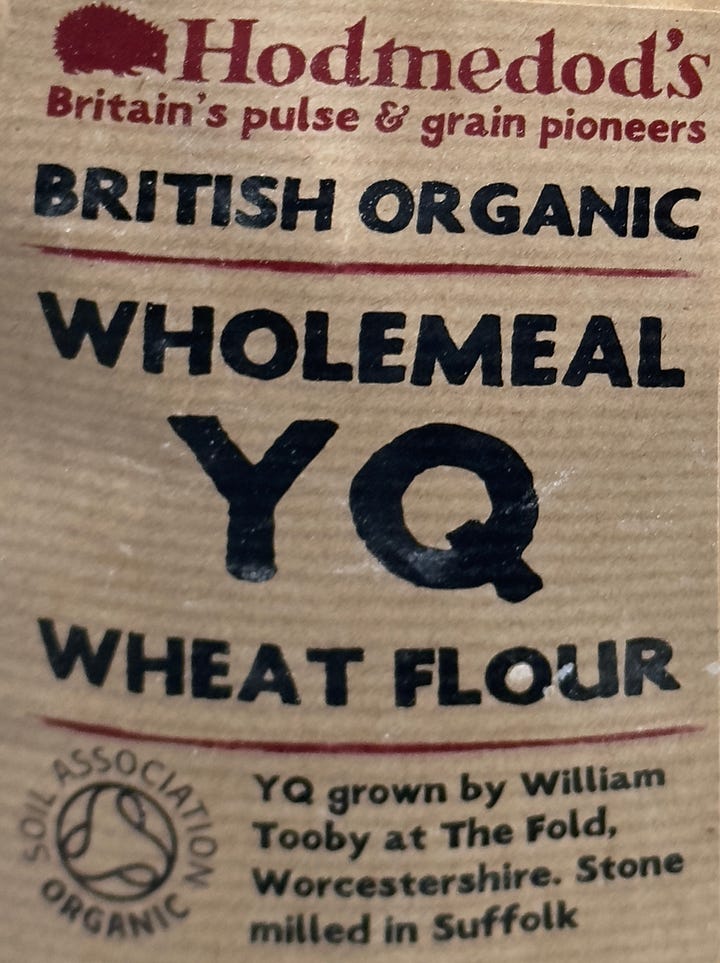

Ursa Minor bakery uses organic white flour alongside speciality stoneground flour, grown in the UK and Ireland, to create a huge depth of flavour and bread with as much nourishment as possible.

Ursa Minor’s best selling sourdough Country loaf is made using organic strong white flour from Shipton Mill and 30% stoneground, wholegrain from Gilchesters and Manna Heritage Mill, grown in the UK and Ireland.

Currently, the flours Ciara and Dara source are 70% British to 30% Irish. Their longer term aim is to move towards a higher percentage of native Irish grains and flours.

It is said that these older, heritage grain varieties have more minerals and nutrients; are easily digestible; are more flavourful and usually better for the soil and the environment.

Historically, Ireland was self sufficient in milling wheat production. However, it had been thought that growing wheat grains is more challenging on the island of Ireland due to our unique mild yet wet weather system.

Yet, one must question whether the globalisation of wheat production and the easy availability of cheaper wheat and flour imports from Canada, Kazakhstan and Ukraine is a significant factor?

Professor Michael Wallace, University of College Dublin, in his 2020 report for Tillage Industry Ireland, shared that since the closure of the commercial Odlum flour mills in Dublin (2012) and Cork (2009), only a handful of mills exist on the island of Ireland today. In 2018, Irish imports of flour from overseas exceeded 200,000 tonnes with a value of €80 million.

Janine Kennedy (Irish Farmer’s Journal, 15 May 2024) reported that in 2023, 69% of flour came from Britain.

Dara mentioned Seamus Jordan, from Borris in South Carlow, who set up his business, Plúr Mill & Bakery, in his parents’ back garden in 2021. Plúr is the Gaelic word for flour.

Seamus originally trained as a chef and previously worked in the Firehouse Bakery, County Wicklow and completed a work placement at the famous Tartine bakery in San Francisco.

Photo: Roger Jones, Irish Independent, Seamus Jordan

In 2023, Seamus wanted to expand so he built a mill on an acre of land he had, and he decided to grow his own flour.

What’s the best possible way to produce good bread? We needed to produce the best possible flour - which is Irish and organic…

…I thought feck it, why not grow my own grain?

In his first year, Seamus sowed, grew, harvested and milled four wheat varieties: purple wheat, blue wheat, Mariagertoba and Ölands. He found that the Mariagertoba grain variety produced the better flour to bake with.

Dara also mentioned two brothers, Fintan and Turlough Keenan, regenerative grain farmers and flour millers, who set up Manna Heritage Mill in May 2022, outside Castleblaney, County Monaghan. Here, Turlough grows over 60 heritage grain varieties and produces stoneground, organic, heritage wheat blends fine sifted flours, on what was historically a traditional small family beef and dairy farm, initially run by their mother and their maternal grandmother before that.

Meanwhile, Fintan runs a 60 hectare organic farm on Bakkegården near Gyrstinge, close to Copenhagen in Denmark, where he grows and mills 17 wheat varieties that were historically grown in Denmark. Fintan also designs and builds mills around the world.

If you are passionate about farming; the biosecurity of foods, and grains in particular; the value of biodynamic growing and the essential role of soil condition, then you may well enjoy this Heritage Radio Network podcast interview with Fintan Keenan. Fintan argues for community based agriculture, with regenerative, no till, local grain growing. In the podcast, Fintan considers the important question that given climate change and global conflicts, should Ireland grow more grain for human consumption, developing greater self-sufficiency?

Photo: author, Some Einkorn grain grown as an experiment by Dara, in their garden in summer 2024.

Einkorn is an ancient wheat grain that almost became extinct. It has about 30% more protein and 30% less starch than flour made from modern wheat. Einkorn is also richer in carotenoids, the natural red, yellow, or orange pigments that are found in many vegetables and fruits. Carotenoids have the medical properties that help in preventing serious diseases. Einkorn also has 30% more phosphorous, manganese, zinc, B6, magnesium, and potassium when compared to modern forms of wheat. All wheat that we consume today is descended from einkorn wheat which has about 14 chromosomes as compared to other kinds of wheat which have 28 to 42 chromosomes. This is important since some studies show that ancient wheat, with its fewer chromosomes, has lower levels of gliadins. Gliadins are proteins that can cause sensitivities in those who struggle with gluten.

Ursa Minor Bakery White Sourdough Bread Recipe:

Equipment:

Glass or Metal mixing bowl

(You can use a ceramic mixing bowl, but it will be very heavy in your hand, when rotating the bowl during mixing.)

Plastic Dough scraper

Metal Bench scraper

Digital Scale

Measuring jug

Instant read digital thermometer

Parchment paper

Banneton (round or oval) proving basket or a baking tin sprayed with oil

A clean tea towel to cover dough when proving and an additional one to put inside your bread banneton (if using)

A bread lame or a new, clean razor blade or sharp, serrated knife to score the top surface of your dough

Ingredients:

Starter - 190 g (25%)

Strong, white Flour - 750 g (100%)

Buy the best quality you can - Dara says Doves Farm Strong Flour, found in some supermarkets, is suitable.

Water - 510 g (68%)

Salt - 15 g (2%)

This recipe therefore uses a 510/750 (=0.68) 68% water hydration level.

Ursa Minor Bakery has been using the same mother starter culture since 2012, which is fed and refreshed regularly (more about this later in the article).

You need to ensure that your starter is in good condition. It should have been fed regularly, prior to baking. This is because the natural yeast in your starter becomes sluggish in the cool environment of your refrigerator. The yeast must be energised through successive feedings, a process called refreshing, to be active enough to raise your dough.

Photo: author, The Ursa Minor sourdough starter feeder

Your starter should:

Smell like a lightly sweet and sour fresh yoghurt.

If your starter has over-fermented, then it will smell acrid; it will be eye-watering and smell like a beer fermentation. The resultant sourdough bread will be excessively acidic and sharp. If this is the case, you need to refresh your starter and begin again.

Look as though it has a loose silky texture, but not pourable like double cream. Bubbles should be noticeable.

Float. Do a float test. When the sudsy bubbles on the surface of a starter form a dome and it appears on the verge of collapse, drop about a teaspoon of starter into a small bowl of room temperature water. If it floats, the starter is full of carbon dioxide gas and ready to use (ripe). If it sinks, let it sit, checking every 30 minutes, until you see even more activity and then try the test again.

Photo: Pinterest, if the sourdough starter floats to the top, then the natural yeast in the starter is active and creating CO₂, so the bread will rise.

Method:

Add 500g of warm water (32 degrees Celsius) to your mixing bowl

Mix your starter into the warm water

Add 750g of strong white flour and mix thoroughly in your bowl with your plastic dough scraper, until no dry ingredients remain. The curve on your dough scraper should follow the inside curve of your mixing bowl, as you rotate the bowl with your non-dominant hand and scrape and mix the dough with your dominant hand.

At this stage, your dough mixture has insufficient elasticity. According to Hooke’s Law, the spring constant k, is too low and the dough breaks as it goes past its elastic limit.

With subsequent folding, fermentation and proving, your sourdough will develop a higher elastic limit, allowing the dough to be stretched further without breaking. This happens because the gluten is stretched by the activity of the yeast to the limit of its elasticity, at which point the dough will have roughly doubled in size.

Beyond this, the dough noticeably loses its structure and elasticity; it will start to look flaccid and a bit holey. This is not a disaster, but the dough will be a little weaker for it.

Claire Saffitz, who writes about sourdough baking for the New York Times, describes the sourdough starter as the “life force” of your sourdough bread and the stretchy gluten strands as “the backbone”.

When two proteins in flour come into contact with water, gluten forms a network inside the dough, trapping the gas produced by the yeast. When flour and water are mixed and allowed to rest, the autolyse process is used to form lots of gluten bonds, that create the basic structure of the dough.

Allow your dough to rest, covered, for 10 to 15 minutes.

Add remaining warm water (10g) and crushed sea salt or kosher salt (do not use salt with anti-caking agents) and mix thoroughly again, to incorporate the salt.

Cover again and leave to ferment. Mark where the dough hits the side of the bowl with a sharpie pen or tape. Note the time, and the temperature of the dough. It should be between 24.5 and 26.5 degrees Celsius.

The bulk fermentation is the dough’s first rise: it’s the time period that begins when the dough is first mixed (step 3) and ends when it is shaped (step 10).

After half an hour, give your dough a turn in the bowl (see video clip below). You need to complete 2 full 360 degree rotations, lifting and folding your dough like a Japanese wave, every 90 degrees. This step is essential as it will create a bubbly, lighter texture in your baked bread.

The folding of the dough reminds me of one of those huge tsunami like waves, as seen in The Great Wave off Kanagawa, 神奈川沖浪裏, Kanagawa-oki Nami Ura, by Japanese ukiyo artist, Katsushika Hokusai, created in late 1831.

Image: Katsushika Hokusai, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Video: author, Dara folding the dough by rotating the bowl and folding at the 4 corners of the circle: N-S-E-W. Two x 360 degree rotations. This will contribute to the resultant texture of your sourdough bread - the air bubbles create a texture full of holes.

Photo: author, dough after the first N-S-E-W corners of the circle “wave” folding

Continue giving your dough a turn every half hour for around 3 hours. Each time you fold the dough, it should feel lighter and sit higher in the bowl. Ideally, you should aim for 4 x 2 revolutions with a N-S-E-W Japanese wave fold in your 3 hour proving period.

Ideally, your dough should be between 24.5 and 26.5 degrees Celsius. If your dough is above or below this optimal range, just remember that it will accelerate or slow the bulk fermentation accordingly. If fermentation seems very slow, you can move your dough to a warmer place, like the inside of the oven with the oven light on.

Once your dough is fully fermented, gently turn it onto a lightly floured worktop, letting its weight coax it out of the bowl and loosening the sides with the bench scraper. Cut and scale it to the size required.

Now roughly shape your dough by taking it for a walk, creating the pre-shape. Pre-shaping the dough guarantees uniform loaf size and helps to organise the gluten strands roughly into the final shape of the baked loaves. The following rest period relaxes the gluten and makes final shaping easier, leading to bread with a better overall rise.

Video: author, Dara shaping the dough by using his scraper to “walk” the dough in a J shaped path, creating the pre-shape

If using a banneton proving basket, place a clean T towel (Richard Bertinet recommends linen) inside and flour generously. If you do not have a Banneton proving basket, you can improvise by using a clean colander and tea towel. Alternatively, if using a rectangular baking tin, spray with oil. During this masterclass, I did both.

Photo: author, Flour your clean linen covered banneton proving basket generously, before the final folding of your sourdough

After a short bench rest (5 - 10 minutes), you are going to complete the final fold and then shape your loaf as desired (see 2 video clips below - the first for a circular banneton and the second for a rectangular baking tin).

The final fold involves uncovering one piece of dough and lightly dusting the top with flour. In one decisive movement, use the bench scraper to lift and turn the dough over, floured-side down. Slide your fingertips beneath the dough and stretch it gently into a square/rectangular shape.

Fold the left side of the dough inward toward the centre, then fold the right side inward and over the top of the left fold.

Starting at the end closest to you, roll the dough away from you into a bulky spiral.

Let the dough sit for a minute or two on its seam to help it seal, then use a bench scraper to lift up the dough and place it seam-side up in one of the prepared banneton proving basket. Lightly dust the exposed part of the dough with a little more flour, and cover with a kitchen towel.

Repeat the same final folding process with the second piece of dough. But, when shaping, use the snow plough technique if this dough is going into a baking tin, seam side down.

Let’s watch that again in a short video, with commentary from head baker Dara:

Video: author, Dara completing & explaining the final folding of the sourdough. The only difference in this video clip is that the final shaping is for placing the sourdough in a floured rectangular proving basket, rather than a circular proving basket

Now prove the dough for 2 to 3 hours at room temperature or place in the fridge for 12 - 18 hours. The longer the dough spends in the fridge, the tangier the final bread will taste

Proving is essentially the second rise — the phase after the dough is shaped.

Check if dough is proved (the poke test). Press a floured finger about 1/2 inch into the dough. If the dough springs back immediately, it needs more time — check again every 20 minutes. But, if it springs back slowly and a slight impression remains, the dough is proved.

Once you are ready to bake, flour a baking sheet or peel and the seam side of the banneton dough with semolina flour and turn your proved sourdough out of the banneton proving basket seam side down.

Photo: author, sourdoughs created by students in the class, waiting to be scored using a lame blade, before being placed in the very hot oven.

Score the top of the loaf with a sharp knife or lame, make a long, slightly off-centre slash about 1/4-inch deep, angling the blade toward the midline of the loaf.

“Lame” means “blade” in French. The lame allows the bread to expand in a controlled manner during baking, preventing it from tearing or becoming misshapen.

The depth, angle, and pattern of the slashes influence how the bread opens up while baking. So, whilst it might seem like a simple aesthetic act, the technique behind the lame’s use is essential for the final outcome of your bread.

The cuts enable a controlled ‘burst’ of the dough which has two main purposes: it increases the surface area of crust where much of the flavour comes from, and it looks attractive.

In the past, when ovens in family homes were non-existent, you could place a distinctive identifying mark on your bread dough, before you took your bread to the communal village oven to be baked.

Load into a pre-heated 250 degree Celsius oven, place a tray with water or ice cubes at the bottom or use a water squeezey bottle to create steam. The steam will enhance the crust on your baked bread.

Reduce the oven temperature to 230 degree Celsius and bake for 25 - 30 minutes.

Now release the steam from the oven and finish baking until you have a golden, dark crust and you can hear a hollow sound, when you tap the bottom of your loaf of sourdough bread.

Internal Loaf Temperature – Many people say that you need to bake your loaf until your internal loaf temperature reaches 96 -98 degrees Celsius. This should be your ending internal temperature, but your loaf may reach this internal temperature 20 minutes before it is done baking.

Your loaf internal temperature will never exceed 100 degrees Celsius - unless you bake all of the moisture out of the loaf!

Your loaf will reach 100 degrees Celsius and plateau at that temperature, while it continues browning and baking. It is not like cooking a steak where the temperature will keep increasing if you keep cooking after it hits your desired target.

Testing your internal loaf temperature when removing the loaf from the oven is a sensible “failsafe” temperature test, but testing it prior to that is not useful for determining “doneness.”

Using a thermometer to test when sourdough bread is done will only work if the dough has been perfectly fermented. If the sourdough is under fermented, the thermometer will show it as being cooked through, however the bread will still be gummy inside.

Allow to cool for a few hours before cutting.

Photo: author, freshly baked class sourdough loaves

Whole sourdough loaves can be stored uncovered at room temperature for 1 day. Once cut, bread should be stored in paper bags at room temperature and will keep for 5 days or longer. After the second day, it benefits from light toasting.

Lunch:

Lunch was partaken around our baking tasks, during fermentation and proving intervals. A tasty and generous meal was provided by Ciara, using predominantly local, sustainable foods. There was a sparkling salad of small, green lentils, pumpkin seeds (or were they mung beans?), beetroot, pickled finely sliced shallots (or onions), one of my favourites - St Tola Goats Cheese from County Clare, small capers, (blood?) orange segments, thinly sliced radishes and a tangy dressing. The salad was that good - I could have just eaten it on its own. This was accompanied by crisp wholemeal pastry, encasing a soft creamy spinach, potato and cheese tart.

Afterwards, there was a divine almond & spelt sponge, with poached new season forced pink rhubarb, sitting on top of a slightly tangy, light creamy vanilla infused layer of gently whipped crème fraiche and/or yoghurt, I think.

Sourdough Focaccia:

Dara also taught us how to make a sourdough focaccia, using a starter based on 40g strong white flour, 40g whole wheat flour, 80g water and 40g of the basic sourdough starter.

The final dough contained 525g strong white flour, 370g water, 12g extra virgin olive oil, 160g starter, 13g salt and an additional 25g of water to dissolve the salt.

This resulted in a higher hydration level of 395/525 (=0.75) 75%.

The fermentation and folding methods are similar to the white sourdough bread.

This much higher hydration level produces greater stretchiness in the dough (or a higher spring constant k value, as we physicists would describe it according to Hooke’s Law). This higher hydration level also gives the dough a beautiful shine, as seen in my photos above.

Rye Sourdough Bread:

The final sourdough bread that Dara taught us how to make was a rye bread. This bread has a unique flavour and is very low in glutens.

The rye starter is adapted from the basic sourdough starter. It is very important to make sure your rye starter is active before you start making your rye bread. For this reason, take your rye starter out of the fridge and feed it several times before leaving for 12 - 24 hours.

The beauty of this sourdough rye bread is that it once you have mixed your ingredients together to form a rough dough; left it for an hour to ferment before shaping the dough and placing in an oiled baking tin and leaving it to rise for another 2 hours, there is no further folding and shaping, in contrast to your basic white sourdough bread.

Starter Maintenance:

There are many articles and videos online with respect to how to make your sourdough starter from scratch.

Earlier, I promised I would discuss how to maintain your sourdough starter.

Looking at the White Sourdough Bread recipe earlier, you need 190g of starter to make your dough and 50g of starter to carry over as your starter to keep it going, so that’s approximately 250g in total.

To feed your starter:

50g starter (discard the rest or use it to make your sourdough loaf or pizza bases or breadsticks)

Add 100g flour (50g strong white + 50g wholemeal)

Add 100g water

Mix it to form a rough dough

Cover your dough with clingfilm or lid and leave at room temperature.

Depending on how regularly you are baking will dictate how often you feed your starter.

If you aren’t planning on baking today or tomorrow, after about an hour or two, once your starter begins to bubble and rise, pop it in the fridge.

To prepare to bake with your starter:

Take it out of the fridge a few mornings before you need it and give it a feed (following the instructions immediately above) with lukewarm water and leave at a warm room temperature.

Feed it again that night with lukewarm water and leave at room temperature.

The next morning it should be more predictable, bubbly and ready to use.

If not, feed again until fully active.

Reflections:

Dara is a self taught baker and this I think has only enhanced his abilities as a teacher. For example, when teaching us how to lift and fold the sourdough, he demonstrated to us three times, with lots of explanation from him and questions from us. Then, very cleverly, Dara asked each of us to demonstrate back to himself and the whole group how to lift and fold the sourdough. With eight students in the group, working in pairs on each of the four work tables, this gave us as the learners eleven repeat times to watch the process; make mistakes and ask questions.

Dara was very generous of his time, his knowledge and his baking skills. And his genuine love for baking and sustainable foods shone through. For £130, all materials, detailed written recipes to take away with us, four loaves of different sourdough bread made of high quality heritage grains and a sourdough starter to bring home and a delicious lunch included, this one day 9am - 5pm Sourdough Bread Making Class, set on the stunning north Antrim Causeway coast was exceptional good value, high quality and great fun. Thank you Dara.

Photo: author, My four loaves of sourdough bread

Thank You for reading Free-Styling @60.

Clicking the heart, sharing and/or commenting below all help other people find my work.

If you have enjoyed my writing and aren’t already a subscriber, please do sign up here - it’s free.

A really wonderful article ,a celebration of a very important skill bread making ,which is of global importance to millions of people around the world.

It shows how bread made in this way is akin to an art form

Well done and the authors bread tasted lovely

The interior of that Ursa Minor Bakery loaf looks so appetising, Caroline. Never tried making it myself (not even during the pandemic), but find the process strangely compelling, and love a really good sourdough loaf when I can find one locally. (Supermarket versions are always a disappointment.)