Lee Miller

Iconic American photographer and Vogue war correspondent in France during World War Two

Introduction:

I was inspired by Anne Boyd’s excellent, Substack article on Lee Miller below,

to drive down through the back roads, the golden autumnal leaves and sunshine of Kent and East Sussex, to visit the photographic exhibition Lee and Lee at Farleys House and Gallery, Muddles Green,

Chiddingly last Friday. It was a 2 hour drive there and back - but it was worth it.

Lee and Lee exhibition, Farleys Gallery https://www.facebook.com/share/p/sANbhBGzTVuXFGiu/?

The following day, I attended the film LEE, at the Gulbenkian Theatre, University of Kent, Canterbury, with my husband.

Lee Official Theatrical Trailer 2024

The film is directed by Ellen Kuras and stars Kate Winslet as Lee, along with Andy Samberg (David Scherman); Alexandra Skarsgard (Roland Penrose); Marion Cotillard (Solange D’Ayen); Andrea Riseborough (Audrey Withers) and Josh O’Connor (Antony Penrose).

Whereas Anne Boyd’s article focusses on Lee Miller’s relationship with Man Ray in Paris and her personal review of the bio fictional novel The Age of Light by Whitney Scharer, I was most inspired by her war correspondent photography, writing and activity in France during the Second World War in 1944 - 1945. And this is what I wish to write about and share with you today.

What an iconic woman. As Kate Winslet shares in the foreword to the book Lee Miller Photographs by Antony Penrose 2023:

There are so many stories of girls to whom things happen. Lee Miller was a woman who made things happen. I don’t mind admitting I adore her….

….To me, she was a life force to be reckoned with, so much more than an object of attention from famous men with whom she associated. This photographer-writer-reporter did everything she did with love, lust and courage, and is an inspiration for what you can achieve, and what you can bear, if you dare to take life firmly by the hands and live it at full throttle.

Childhood and early Career:

I feel you need some background information about Lee to understand her complex, complicated and compelling World War 2 story better.

Lee was born into a well to do family in Poughkeepsie, upstate New York in 1907. Her childhood was far from idyllic - traumatic would be a better descriptor. Lee’s father Theodore, an engineer and amateur photographer, very questionably photographed her nude as a child and teenager. From this, Lee learnt how to develop film and make prints. At seven years old, Lee was raped by a friend of the family and consequently contracted gonorrhoea. Her parents warned Lee that she was not to speak about this to anyone - and she didn’t - for decades.

Lee was enrolled and expelled from several schools. At 18, she visited Paris with two chaperones, on route to finishing school in Nice, and is reported to have said:

Baby, I’m home!

Lee absconded from her chaperones and never arrived at finishing school, instead enjoying la vie parisienne. Lee’s father went to Paris to escort her home. Returning to the US in 1926, Lee initially studied Art in New York, but found it unchallenging. Her son Antony Penrose quotes Lee as saying:

Painting is a very lonesome business whereas photography is a more friendly affair. What’s more, you have something in your hand when you’re finished - every 15 seconds you’ve made something. But when you’re painting, you wash out your brushes at the end of the day and retire in disgust with little to show for it. ..And you have been lonesome all day as well! Whereas with photography as long as you can afford another piece of film you can start over again you see.

In 1927, it was rumoured that Lee deliberately walked across a road in front of a car in New York, when she recognised Condé Nast, the owner of Vogue magazine. He pulled her away from an oncoming car; Lee fainted in his arms and a few weeks later, she was on the front pages of Vogue. So began Lee’s modelling career, even before she was twenty years old. She became what we would describe today as a supermodel, so popular was Lee.

Lee Miller as the archetype of the stylish moderm woman. Cover art by Georges Lepape, Vogue, March 15, 1927

In a Vogue online article titled Everything You Need to Know About Lee Miller—in Vogue and Beyond by Laird Borrelli-Persson 11/09/23 , she describes Lee on that front cover:

her cloche-covered head and pearl-wrapped neck dominate the cityscape; Miller is presented as the epitome of the modern woman; powerfully beautiful, streamlined in the Deco fashion, and slightly androgynous.

Photo: Edward Steichen: Lee Miller modelling for Vogue 01/09/1928

Lee learnt much about photographic techniques from Vogue’s chief photographer Edward Steichen.

However, later in 1928, Miller’s career took a turn when her photograph was published with an advertisement for Kotex sanitary pads. It was the first time a recognisable woman had posed in an advertisement for menstrual products. This was viewed as quite shocking at the time and effectively ended Lee’s modelling career.

Photo Edward Steichen: Lee Miller in an advertisement for Kotex 1928, Museum of Menstruation

However, Lee viewed it as an opportunity to pivot. In an interview with The Poughkeepsie Evening Star, 01/11/1932, Lee said:

I would rather take a photograph than be one.

Lee travelled to Paris, and with an introduction from Edward Steichen, she became the student, muse and lover of the surrealist photographer Man Ray. Their relationship was tempestuous, but Lee learnt much from Man Ray; refining her surrealistic style and together they developed the innovative solarisation technique. She also collaborated with the likes of Pablo Picasso and Jean Cocteau.

In autumn 1932, Lee returned to New York, setting up her own successful photographic studio, despite the economic depression. Her clients included Elizabeth Arden, Saks Fifth Avenue and Helena Rubinstein.

Yet, Lee missed the freedom and artistic stimulation of Paris. When an Egyptian business man Aziz Eloui Bey, whom she had met earlier in Paris, arrived in New York and proposed to Lee in 1934, she accepted and spent the next three years in Cairo, Egypt. It is in Egypt, where Lee produced some of her most artistic work, including her famous Portrait of Space,

Photo Lee Miller Portrait of Space 1937, Turner Contemporary Gallery, Margate, Kent April 2018

travelling into the desert, ‘looking for new oases, for lost villages, for traces of unknown civilisations’ (Vogue interview 1974), free of commercial commitments.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Lee grew bored with the languid, expatriate life in Cairo. In 1937, she flew to Paris - reconnecting with her friends and meeting Roland Penrose, an English artist, historian and poet. They fell in love and Lee eventually became his wife and mother of their child Antony Penrose.

Lee Miller & the outbreak of World War 2:

By 1939, Lee has amicably separated from her first husband Aziz Eloui Bey and was living with Roland Penrose in England.

In the opening shot of the film LEE, we meet a shell-shocked Lee in the midst of gunfire in St Malo, Brittany, France in 1944. The camera zooms in on an image of an abandoned military boot and ammunition, which Lee is attempting to photograph.

Photo Lee Miller: Boot and ammunition, St Malo, Brittany, France 1944 https://www.facebook.com/share/p/HtqYNKXnHXumQNZD/?

I am so glad I visited the Lee and Lee photographic exhibition before I watched the film LEE - because I can appreciate better how the director (Ellen Kuras, cinematographer Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind 2004) and the film editor very cleverly used film shots to reference many of Lee Miller’s photographs in the film. Indeed, the photographic exhibition Lee and Lee places comparative images of Lee Miller’s wartime reportage directly next to both photographs by Kimberley French (official photographer for LEE) and photographs by Kate Winslet, taken on set whilst filming, using a Rolleiflex camera that was carefully researched and compared with Lee Miller’s own camera at Farleys.

The film then switches to an 1977 interview with, who I initially think is, a male journalist (Josh O’Connor) in Lee and Roland’s Farleys House. You can see Lee pouring herself a glass of gin and lighting a cigarette. The interviewer asks “What do I get - a transaction?” Lee responds “A story - you tell me, I tell you”.

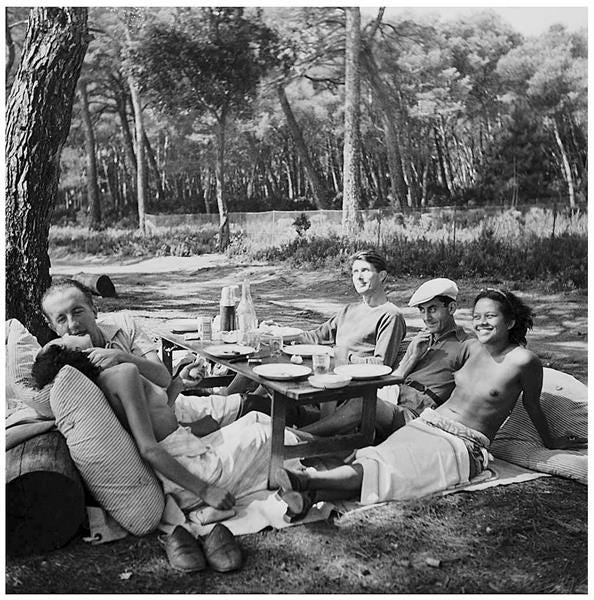

The film then goes back briefly to 1937, in the south of France. Lee has only recently met Roland Penrose. She is having a picnic lunch with her French friends and Roland arrives, pouring himself a glass of wine, before being offered.

Photo Lee Miller: Île Sainte-Marguerite, Cannes 1937 Wikiart https://www.wikiart.org/en/lee-miller/picnic-ile-sainte-marguerite-france-1937

Left to right - Nusch and Paul Ėluard, Roland Penrose, Man Ray, Ady Fidelin. Penrose, a British surrealist painter had met Lee a few weeks earlier and fell madly in love with her.

This photograph exudes carefree happiness and reminds me of Edouard Manet’s painting Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe 1863 in the Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

Later, the group of friends discuss the rise of Hitler, when the news reports Hitler’s 48th birthday procession. From then on, the film oscillates between the 1977 interview at Farleys House and World War 2.

Returning to 1977, the interviewer asks Lee how could they not see what was coming with Hitler’s rise to power? Why did she leave Paris and return to London with Roland? Lee replies “occupation”.

In the next film scene, we see Lee feeling useless in London in 1939. She needs a focus. Lee arrives without an appointment at the Bond Street Vogue office. Audrey Withers, Vogue editor in Britain, is with Cecil Beaton.

Photo Georgina Slocombe: Staff working in the Vogue office, Bond Street, London bomb cellar during the second world war. Audrey is standing on the left in a hat. The Guardian https://amp.theguardian.com/fashion/2020/jan/28/the-fashion-futurist-how-vogues-wartime-editor-revolutionised-womens-lives

Lee asks for a job with Vogue. Cecil Beaton says “we don’t hire older women as models”. Lee shows Audrey her portfolio of Syrian model photos. Lee has not been active in professional photographic work for 5 years and initially there are no available positions. However Audrey eventually offers her a role at Vogue in 1940.

Photo Lee Miller: Sandra models for Pidou, Vogue studio, London 1939 https://www.facebook.com/share/NXgFLwdaNu7aKVep/?

Lee’s photographic work for British Vogue during the Blitz in London combined traditional women’s fashion images with many surrealistic ‘found images’, often photographed outside on the streets, due to bombing or power cuts, with Lee looking for alternative locations.

Photo Lee Miller: Fire Masks, London 1941 https://www.facebook.com/share/p/QohY8AskBGSsFtuh/?

Audrey Withers encouraged Lee to expand her Vogue remit by photographing the women of Britain at war. In her memoir Lifespan (1994), Audrey wrote:

The proper business of a magazine is to reflect the life of its times. In a time of war, we needed to report war, and Lee Miller might have been created for the purpose of doing just that for us.

Lee became very good friends with Audrey Withers and many years later confided in her about her traumatic childhood.

The film returns to the 1977 interview. The interviewer asks Lee “You never wanted children?” Lee responds “I didn’t know I could. I could never be a good mother”.

Returning to 1942 in the film, Lee and Audrey are discussing why British women are not allowed to go to the front line in Europe. Lee asks Audrey to ask the British government for permission again.

David E. Scherman, an American, became a highly distinguished combat photo-journalist and the longest serving staff member for LIFE magazine(1936 - 1972).

Photo Lee Miller: David E Scherman Dressed for War, London 1942 https://www.facebook.com/share/p/QDhLQ5RcrZAFJ9mD/?

David Scherman met Lee Miller in London in 1942. They became friends and lived together in Hampstead with Roland Penrose until D-Day. It was David who suggested to Lee that she should use her American nationality to apply to the US government, to get permission to travel to Europe as a war correspondent for Vogue.

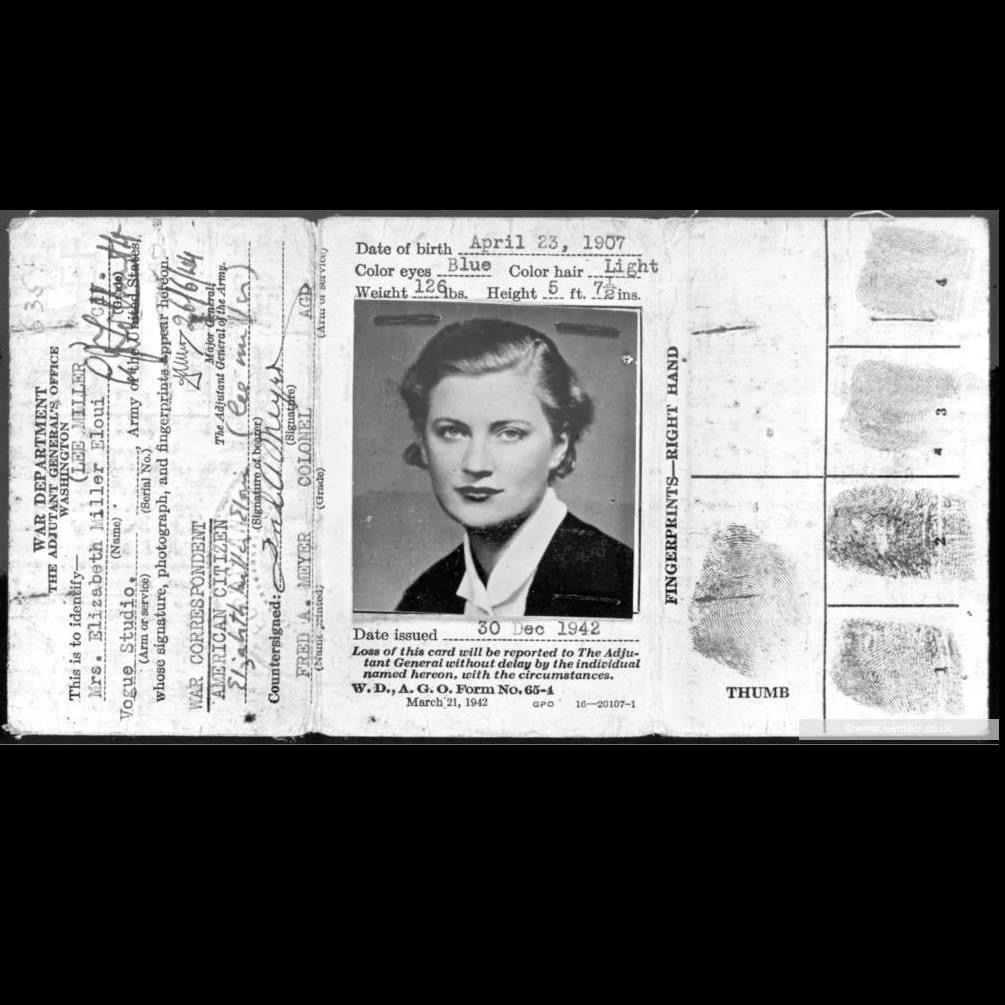

Photo unknown: Lee received permission to become an American WW2 war correspondent US Army Identity Card on 20/12/1942 https://www.facebook.com/share/p/YpVHSN1UJfqt6nhJ/?

Lee received her US Army identity card as an American war correspondent in December 1942. At that stage, female war correspondents were not allowed in to military debriefings.

Lee visited a US Army nurses' billet in Oxford, England for the May 1943 issue of British Vogue. She had started to explore photojournalism, with a particular interest in capturing women's experiences of the conflict.

Photo Lee Miller: US Army nurses' billet, Churchill Hospital, Oxford 1943, https://www.facebook.com/share/p/GBsyyVscb3bzp4mm/? 22/09/23

I just love this photograph - in fact, it is my favourite one in the Lee and Lee photographic exhibition. As a veterinary nurse, I can understand the urgent need to wash and dry your uniform and underwear after a long, late shift because you need it in 8 hours time, when you wake up for your next shift. Interestingly, in Lee’s original photograph, you can see that the knickers are practical and functional grey - white cotton big girls’ pants for serious work - not the skin tone, silky, with the slightest hint of frivolity knickers of Kimberley French’s photograph.

In the film LEE, Cecil Beaton, Vogue London, objects to publishing Lee’s photo of these knickers. Audrey insists - “only a woman could have taken these photographs”.

Lee’s first war correspondent assignment in France:

Accredited female war correspondents were finally given access to visit war zones in July 1944, a few weeks after the 6th of June D-Day landings. Lee’s first war zone assignment was to document an evacuation hospital near Omaha Beach, Normandy, France.

This was Lee’s first return visit to France since WW2 had begun. In her opening article in the 15th September 1944 edition of Vogue, Lee wrote:

As we flew into sight of France I swallowed hard on what were trying to be tears, and remembered a movie actress kissing a handful of earth. My self-conscious analysis was forgotten in greedily studying the soft, grey-skied panorama of nearly a thousand square miles of France - freed France…

…It was France. The trees were the same – with little pantaloons like eagles; and the walled farms, the austere Norman architecture.

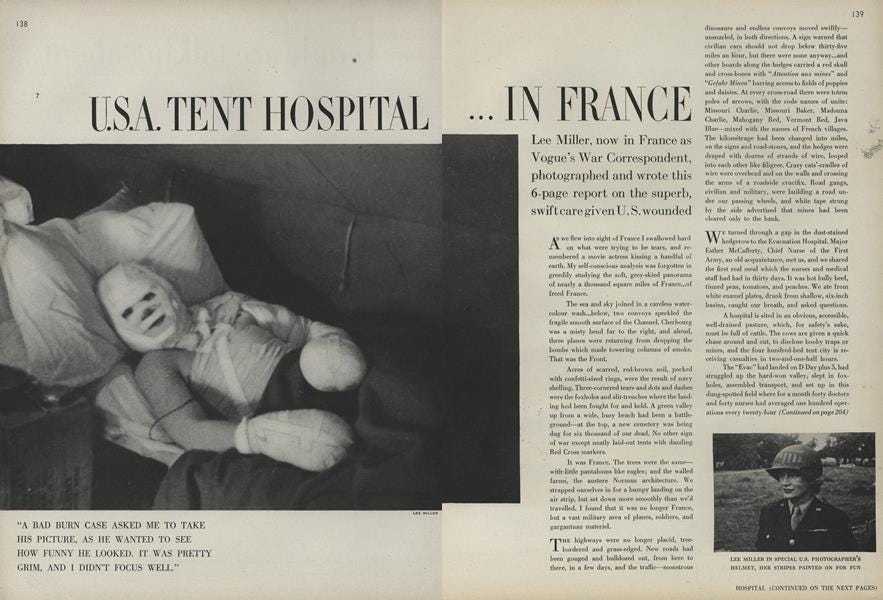

Image Vogue Archives: U.S.A. Tent Hospital …in France https://archive.vogue.com/article/1944/9/usa-tent-hospital-in-france

In her dirty and creased uniform, Lee threw herself into her work, covering two tent hospitals in 35 rolls of film; taking 100 + surgery photographs per day and almost 10,000 words in just five days.

Photo Lee Miller: Tent operating theatre at 44th Evacuation Hospital, Normandy 1944 https://www.facebook.com/share/p/kDhC1uRhmf1D3CYh/?

Roland wrote every week asking her to come home.

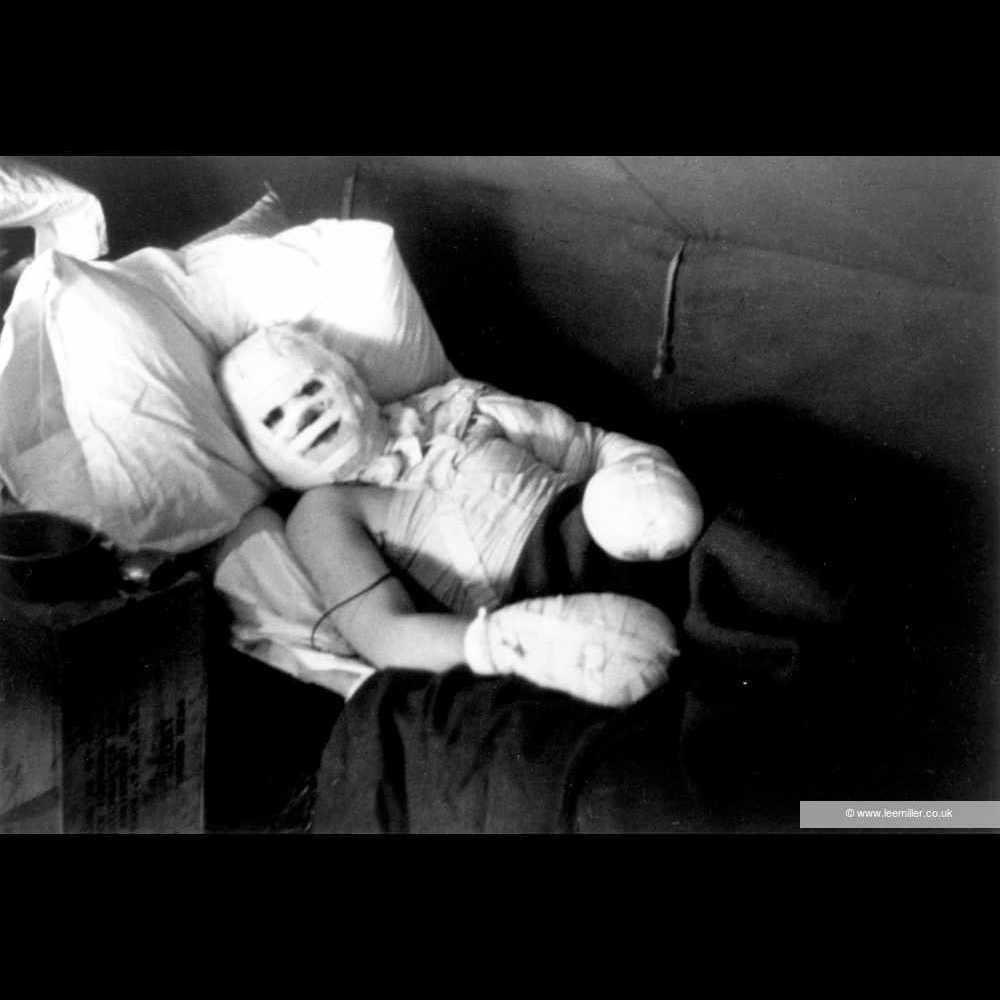

In the film LEE, Kirk, a badly injured and bandaged soldier, asks Lee to take a photo of him. He wants his family back home to see how brave he is. Lee admires the bandaged man’s eyes.

Photo Lee Miller: Bad burns case at 44th Evacuation Hospital Normandy, 1944 https://www.facebook.com/share/p/1fMZn38btU84hyXs/?

Lee Miller, in her dispatch titled ‘Unarmed Warriors’, published in US and British Vogue on 15 September 1944, Page 138.

A bad burns case asked me to take his picture as he wanted to see how funny he looked. It was pretty grim and I didn’t focus good.

Lee’s second war correspondent assignment Omaha beach, Normandy, France:

Eager to return to the action, Lee returned a second time to France, aboard a US Navy tank landing ship in August 1944. Half-way across the Channel, the ship’s route was changed from Utah Beach to Omaha, where it ran aground at high tide.

Photo Lee Miller: View up the beach from LST [393], Omaha Beach, Normandy 1944 https://www.facebook.com/share/p/SbTvnbhvseTuhhv2/?

Photo Lee Miller: The LST 371 Crew wait for land to dry out, Omaha beach, Normandy 12 August 1944. https://www.facebook.com/share/p/tHQvX4v1Jj6fn7jW/?

Lee’s war correspondence during the Siege of St Malo, Brittany:

In the film LEE, a colonel tells her to go to St Malo and to write her obituary before she goes to the frontline.

August 13 - 17, 1944, the date of the city's liberation by the 83rd Infantry Division of the United States.

The American Forces Information Service agreed to accredit Lee and escort her to Saint-Malo, where she was supposed to report on the "day after" with military intelligence having confirmed that the area was secure.

However, in contravention of her war correspondent accreditation, which did not allow female photojournalist into active combat zones, Lee arrived in St. Malo on 13th August 1944 in an active conflict zone.

Lee, with her Rolleiflex camera around her neck, captured the faces of the Saint-Malo residents, evacuating their bombshell destroyed homes; GIs with fearful expressions and the Nazi prisoners humiliated by defeat but thankful to be alive.

In the film LEE, David Scherman advises Lee to worry about writing the truth first, worry about it being good later.

Lee’s reports, edited and published for the readers of Vogue, balance factual observation with her personal testimony.

In October 1944, American and British Vogue published Lee Miller's account of the siege of St Malo, in which she came upon one of the most exclusive coups of her career - the only journalist to witness the early days of this brutal battle.

Photo Lee Miller: Artillery spotters with telephones in Hotel Ambassadeurs directing fire on Grand Bey and St Malo old town, Brittany 1944 https://www.facebook.com/share/pueQyjfAek8i1yPR/?

In this edition of Vogue, Lee wrote:

I thumbed a ride to the Siege of St Malo. I had bought my bed, I begged my board, and I was given a grandstand view of the fortress warfare reminiscent of Crusader times…

The OP [observation post] was in a small, tall, new little hotel, "The Ambassadeurs" ... The rooms had inner-spring mattresses which made for a rather bouncy perch for picture-taking, especially as the artillery bursts made me jump a bit each time. In a beautiful honeymoon room facing the sea a couple of soldiers were lying on a bed with telescope trained on the target, and 'phone connected to their gun and to the command post. There was a spectacular view of old St. Malo burning, of the Fort National (where there were several hundred French civilian prisoners and of the Grand Bey, which was shooting on us.

Photo Lee Miller: Self reflection in mirror, St Malo, Brittany 1944 https://www.facebook.com/share/vxV9jKEkBM8NLaTS/?

Again, I love this photo of Lee. A “selfie”, decades before its modern popularity in the 21st century.

Rennes, Brittany - Lynching of Nazi Collaborators:

Photo Lee Miller: Women accused of Collaborating with the Germans, Rennes 1944 https://www.facebook.com/share/BihVQLA3nKBntYdP/?

In Rennes, Brittany, Lee witnessed the lynching and hair shaving of four local, female informers.

In the film LEE, a local shouts “Dirty collaborating whore” before spitting on the face of one of the lynched women. These women were known as femmes tondues.

Photo Lee Miller: Women accused of Collaborating with the Germans, Rennes 1944 https://www.facebook.com/share/vX5QpHg36E3MaRWe/?

Lee, in her communication with Audrey Withers on 26 August 1944, wrote:

…They were stupid little girls - not intelligent enough to feel ashamed…they’d been living with Hun boyfriends since the first week of the occupation…

…Later, I saw four girls being paraded down the street and raced ahead of them to get a picture. In that I was then leading the parade, the population thought a femme soldat had captured them or something, and I was kissed and congratulated while the victims were spat on and slapped.

Lee’s experience of being celebrated as a femme soldat inversely reflects the actions taken upon the femmes tondues.

The Liberation of Paris:

Photo Lee Miller: Barbed Wire Entanglements, Place de La Concorde, Paris 1944 https://www.facebook.com/share/3y38w763QFDid6LJ/?

Lee and David Scherman returned to a liberated Paris later in 1944, but war continued across Europe. In the film LEE, at the Scribe hotel, a package of new silk knickers from Audrey is delivered to Lee.

Photo Lee Miller: Champagne bottles and Jerry Cans on the balcony of Lee Miller's hotel room, Hotel Scribe, Paris, France 1944 https://www.facebook.com/share/xvVPQGaBpayvfA8Y/?

Photo Lee Miller: After the battle of Paris 1944 https://www.facebook.com/share/p/VNJA7xC2m2PzfYBJ/?

Children near the Notre Dame celebrate the liberation of Paris, their playground is a burned out car. Lee wrote:

Paris was starting to clean up after the world’s most gigantic party. The tinkle of glass reminded me of the early blitz days in London.

Paris held a profound connection for Lee. Not only was it the city that first fired her passion for art, where she pioneered Surrealism and honed her photography skills, it was also where she found life-long friendships. When she arrived at the liberation of Paris during WW2, she sought not just to cover the war damage but just as importantly, to find her friends. Many were taken away by the Gestapo, missing or in hiding.

From her hotel base in a newly liberated Paris, Lee oscillated between assignments as a wartime photojournalist and fashion photographer for new haute couture collections, as the fashion capital awoke following German occupation.

Photo Lee Miller: Model wearing Schiaparelli fur-trimmed turban and coat at opening of the Schiaparelli store, Place Vendôme, Paris, France 1944 https://www.facebook.com/share/p/13UMhBk1wfFMQ6BU/?

France Free Again: The Liberation of Paris, Vogue 15 October 1944, https://archive.vogue.com/article/1944/10/the-liberation-of-paris

In the October 15th 1944 edition of Vogue, in an article titled ‘The Liberation of Paris’ Lee wrote about Parisian women’s fashion:

Everywhere in the streets were the dazzling girls, cycling, crawling up tank turrets. Their silhouette was very queer and fascinating to me after utility and austerity Britain. Full, floating skirts, tiny waist-lines.

They were top-heavy with built up pompadour front hair-dos and waving tresses: weighted to the ground with clumsy, fancy thick-soled wedges…

…If the Germans or their Government representatives wore shaved heads…the French grew long hair…If three meters of material were specified for a dress, the French found fifteen meters for a skirt alone…saving material and labour meant help to the Germans… it was patriotic to waste instead of to save.

Photo Lee Miller: Model (Norma Wittig Cooke) with GI’s, Paris 1944 https://www.facebook.com/share/JpRMLhmiZ9cT78B9/?

Photo Lee Miller: For cycling: white rayon dress [modelled by Norma Wittig Cooke], Paris 1944 https://www.facebook.com/share/cc6MZnKfSTwNVJoJ/?

Norma Wittig Cooke was something of a society girl in Paris, but a busy social life didn't stop her from doing her bit during the war. In addition to working as a nurse, Wittig Cooke was an active member of the French Resistance. This image is from a Vogue fashion spread, but Wittig Cooke wasn't a model. She remembered cycling near the Eiffel Tower one day when an American lady stopped her and asked if she'd like to model.

Photo Lee Miller: Couple running veiled Eiffel Tower, Paris 1944 https://www.facebook.com/share/p/drvLBpRjVaQyVtyP/?

Published in British Vogue, March 1945. Captioned as: Paris under the Snow. Lee wrote:

It brought fun to the boys and girls, snowballing; brought hardships, too...made a long toboggan slide of Montmartre...

Photo David E Scherman, Lee Miller with her Rolleiflex 3.5 automat camera, in front of Notre Dame Cathedral, Paris 1944 https://www.facebook.com/share/p/zS6NoswnuB1dBf7B/?

The Journey continues eastwards to the frontline - there are thousands missing:

Lee eventually finds her friend Solange (Marion Cotillard) in her wrecked apartment in Paris. It becomes clear to Lee that many people in Paris have been rounded up by the Gestapo and disappeared.

In the film, Lee phones Audrey Withers from Paris, to share that there are thousands of missing people, taken by the Gestapo. Lee says “It’s not over”.

Roland arrived in Paris. He wanted his wife to come home to London, to look after her.

In the film, Lee refuses, saying people are missing. Lee tells David Scherman that she is heading to the frontline and asks him “Are you ready to go?”

Lee and David Scherman reported separately and together covering the US Forces in Europe as they followed the allied advance after D-Day and the subsequent liberation of Paris, including the Russian – American link at Torgau, the liberation of Dachau, and the fall of Munich.

In the film LEE, there is a scene where Lee is driving to the frontline with David Scherman by moonlight. Lee drinks some alcohol from a bottle and takes some pills to take the edge off, as they drive 500 miles eastwards.

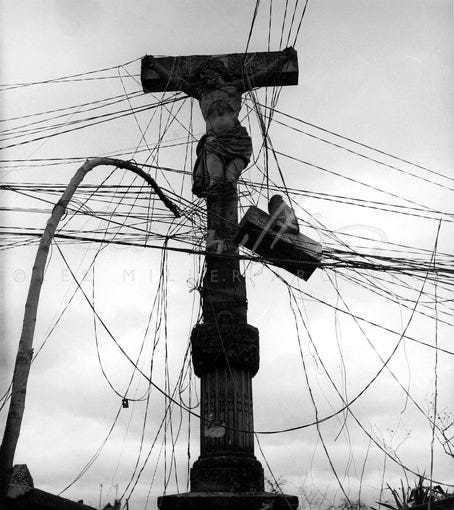

Photo Lee Miller: Hotline to God, Strasbourg, 1945 https://www.facebook.com/share/ojZZs8M7A5TAoxoh/?

In Leipzig, Lee and David Scherman found the deputy Bürgermeister, his wife and daughter, dead at home. They have committed suicide by ingesting cyanide.

Photo: Lee Miller: The Deputy Bürgermeister's daughter [Regina Lisso], Leipzig town hall 1945, Victoria and Albert Museum https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1386661/photograph-by-lee-miller-burgermeister-photograph-miller-lee/photograph-by-lee-miller-b%C3%BCrgermeister-photograph-miller-lee/

In the film, Lee and the interviewer are discussing what Lee found in Germany. She says: “There is so much life in someone’s eyes right up until the moment that there isn’t.”

Continuing their journey eastwards towards the frontline, Lee and David Scherman find trains full of rotting dead corpses. At Buchenwald and Dachau concentration camps, they find horrifying piles of emancipated corpses piled up ready for cremation in the gas chambers. The film shots intentionally replicate Lee’s original photographs of Buchenwald and Dachau concentration camps. The many photographs of the murdered Jewish men, women and children are too horrific to see here. But Lee’s photographs can be viewed at the Lee Miller Archives.

In the film LEE, David Scherman says “All those people, all those people, they were my people”.

This is truly genocide on an unimaginable scale.

Photo Lee Miller: Liberated prisoners in their bunks, Dachau, Germany.1945 https://www.facebook.com/share/Wt7icFz48Eeqh3XK/?

In the cover letter Lee wrote to her editor Audrey Withers, accompanying her manuscripts and photographs of Dachau and Buchenwald concentration camps, she said:

I don't usually take pictures of horrors. But don't think that every town and every area isn't rich with them. I hope Vogue will feel that it can publish there pictures…

…I would be very proud of Vogue if it would run a picture of some of the ghastliness—I would like Vogue to be on the record as believing.

In her manuscripts Lee writes:

The overcrowded blocks of prisoners were recrowded by incoming evacuated prisoners from other camps. The triple decker bunks without blankets, or even straw, held two and three men per bunk who lay in bed too weak to circulate the camp in victory and liberation marches or songs, although they mostly grinned and cheered, peering over the edge. In the few minutes it took me to take my pictures two men were found dead, and were unceremoniously dragged out and thrown on the heap outside the block. Nobody seemed to mind except me. The doctor said it was too late for more than half the others in the building anyway.

American Vogue did publish Lee’s manuscript and photographs, the article was titled ‘Believe It’. British Vogue published one image from the concentration camps.

Audrey Withers agonised over whether her war-weary readers could cope with this, but eventually included one picture, berating herself later for not running as many as the newspapers did.

Lee wrote to Withers:

Dave Scherman and I took off from Dachau. The sight of the blue and white striped tatters shrouding the bestial death of the hundreds of starved and maimed men and women left us gulping for air and for violence, and if Munich, the birthplace of this horror was falling, we’d like to help.

Later that same day on 30th April 1945, Lee and David Scherman entered Hitler’s apartment in Munich. The apartment has already been requisitioned by the US army.

Photo David Scherman. Lee Miller in Hitler’s bathtub, Munich, Germany, 30/04/1945 https://www.facebook.com/share/p/NiC1xEL9NDi3yDBj/?

They found Hitler’s bathroom and there was hot water. Both Lee and David Scherman were keen to take a bath, after weeks without washing, wearing the same clothes. Yet, even as Lee ran the water for her bath, she realised this was a photographic opportunity.

Kate Winslet, in the foreword to the book Lee Miller Photographs by Antony Penrose 2023 says:

It’s a meticulous set-up by a pair of bloodied professionals who knew the power of a picture to tell a larger story. And it was taken using Lee’s camera, not Scherman’s…They were careful to keep her breasts covered, knowing that the image would never get past the picture editor if they were visible. Nevertheless, the image is entirely staged by Lee. The framed photo of the Führer is propped precariously on the sill of the tub, perhaps to signal imminent downfall (Lee and Davie did not know Hitler was already dead). That nasty nude sculpture that nudges into frame might be there as a reminder of a despicable Aryan ideal. And it is surely not by chance that the metaphor for murder is dead centre: Lee’s combat boots - after she had wiped the dirt of Dachau onto the dictator’s silly little bathmat.

The film moves forward to 1977 again. The interviewer asks Lee why did she take the photo in Hitler’s bathtub - was it impulsive? Lee replies that Hitler and Eva Braun were already dead in Berlin.

When Lee returned to London at the end of the war, she visited the Vogue office.

In the film, Lee is angry, upset and disappointed, when she realises that only one of her many photographs of the concentration camps were published by British Vogue. Audrey explains that government ministers didn’t give permission for Vogue to publish the photos. Audrey sent them to New York, hoping that US Vogue would publish them.

Lee Miller after World War Two: Farleys House, a child and a new passion for cooking:

After the war, Lee divorced her first husband Aziz Eloui Bey and married Roland Penrose in 1947. She gave birth to her only child Antony in September 1947. Lee found it difficult to adjust to post war life, without the adrenaline buzz. She eventually ceased her surrealistic photographic work.

In the film, we return to 1977 at Farleys House, where we realise that the interviewer is actually Lee’s son Antony Penrose. He feels that his mother blamed him for everything that went wrong in her life. Lee responds by showing Antony her box of memories, which contains a lock of his hair as a baby and his first drawing. She tells him that she knows she wasn’t a good mother but that she really tried.

In a 2016 interview with The Guardian, Penrose stated that his mother suffered from postpartum depression and struggled with alcohol, very probably due to post traumatic stress disorder caused by her WW2 experience and her childhood abuse.

Kate Winslet, in the foreword to the book Lee Miller Photographs by Antony Penrose 2023 says:

Lee paid an enormous personal price for what she witnessed at war. Her brain became like a camera lens that could never click shut. She could not ‘unsee’ harrowing atrocities she had photographed.

Lee reinvented herself as a gourmet cook, cooking for friends and family. Her son Antony says that David Scherman, in conversation with him in New York 1983, believed that Lee’s cooking food for friends saved her life after the war. Lee owned 2000+ cookbooks. Roland built her a library for her books, in an extension at Farleys House. In The Confessions of a Compulsive Cook, Lee’s friend at Farleys House, Bettina McNulty, says:

Lee chose cooking as much for therapeutic reasons, gaining a real sense of escape in her newly invented career. She felt compelled to put her wartime experiences behind her and had a self-imposed censorship on discussion about her work during the war.

The Entertaining Freezer was meant to be the title of Miller’s unpublished cookbook, notes Antony Penrose, who wrote the introduction to Lee’s granddaughter Ami Bouhassane’s book, Lee Miller: A Life with Food, Friends and Recipes.

Lee died of lung cancer in 1977, before her cooking manuscripts were published. Antony and Roland discovered thousands of Lee’s photographs and contact sheets in the attic at Farleys House, after her death.

Photo Roland Penrose: Lee Miller in Farleys House kitchen, 1955 https://www.facebook.com/share/p/drvLBpRjVaQyVtyP/?

Thank You for reading Free-Styling @60.

Clicking the heart, sharing and/or commenting below all help other people find my work.

If you have enjoyed my writing and aren’t already a subscriber, please do sign up here - it’s free.

Caroline- So many wonderful insights here, but I am particularly pleased to have learned about the Lee&Lee work. Thanks for sharing.

I watched the film on a transatlantic flight a couple of weeks ago and thought it was very moving. I particularly liked the way it emerged that the interviewer was her son. Thanks very much for this comprehensive post, which helped fill in gaps and answer a number of questions that I was left with.