Grania

A play based on the Irish legend Diarmuid and Gráinne; originally written in 1912 by Lady Augusta Gregory; directed by Caitríona McLaughlin, premiering at the national Abbey Theatre Dublin in 2024

Introduction:

I had booked tickets online to see Caitríona McLaughlin’s direction of the Abbey Theatre’s premiere of Lady Augusta Gregory’s 1912 play Grania on 09/10/24, with my sister and nephew/godson.

It had been a sweaty, tachycardiac journey to get there - as my budget Ryanair flight from London was two hours late. We missed our dinner reservation at Xi’an Street Food restaurant, North Earl Street (McKenna guide) - but had time for a quick half pint of Guinness (me) and a hot port (my sister) with a retro packet of scampi fries (me) and a bag of crisps for my sister at the Flowing Tide pub, before the play. My godson and nephew does not enjoy pubs, so he made a quick jaunt over O’Connell bridge to Trinity College’s front gates and archway entrance. When he returned, I shared with him that in October 1982, when I first entered the front gate arches at Trinity during Freshers’ week, I became so nervous of the crowds and noise that I did a U turn, retreated and returned later.

Grania was my nephew’s only second theatre visit - having attended Brian Friel’s Dancing at Lughnasa at the Gate Theatre Dublin, with his first love Spanish girlfriend the previous month. How could we compete with that? - but in retrospect, we might have just done that - more about Adam and Eve later in this article ….

Diarmuid and Gráinne - the Legend:

Diarmuid and Gráinne is one of the great love stories in Irish legends. She is the young, beautiful daughter of the High King of Ireland at Tara. He is the popular, highly skilled, handsome young warrior of the Fianna warriors.

But Gráinne is betrothed to Fionn Mac Cumhaill, the older, experienced leader of the Fianna warriors. When the two young lovers run away together on the eve of that wedding, all three characters suffer the consequences…

Lady Augusta Gregory:

Isabella Augusta Persse was born in county Galway in 1852, one of 13 children.

She married a neighbour, Sir William Gregory of Coole, former governor of Ceylon and 35 years older than her, when she was 28. However less than two years later, whilst in Cairo with her husband, Augusta Gregory met the young, handsome English anti-imperialist poet Wilfred Blunt. They began a passionate affair. So there are parallels in affairs of the heart between Augusta Gregory and Grania.

Painting Jack B Yeats 1903 Wikipedia

The late 1890s through to the early 1900s was a period of great unrest in Irish history, culminating in the 1916 Easter uprising. This was accompanied by a renaissance in Irish literature and art. At Coole Park, near Gort, County Galway, Lady Gregory offered a retreat, hospitality, and encouragement to visiting Irish writers of the time, including George Bernard Shaw, Sean O’Casey, John Millington Synge and George Moore.

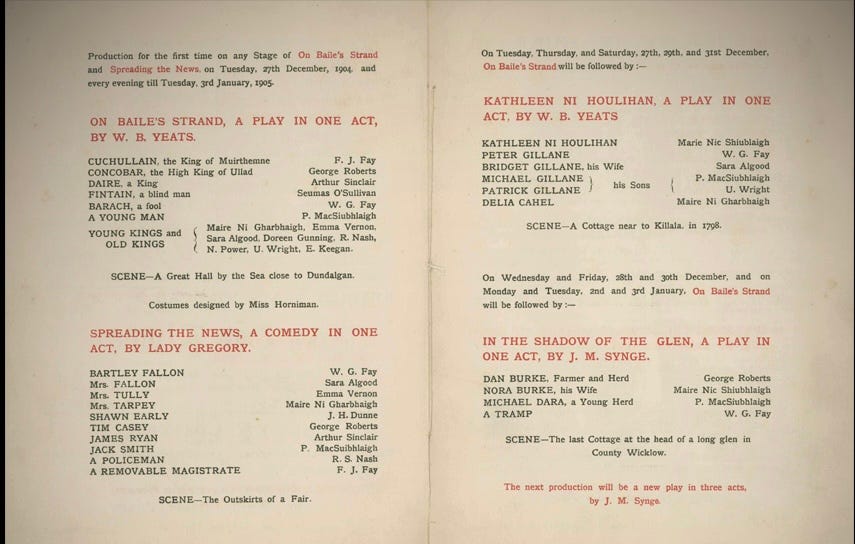

Lady Gregory collaborated with William Butler Yeats, and together with Edward Martyn, they founded the Irish Literary Theatre in 1899. This then became the Abbey Theatre in 1904, Edward Martyn having departed. Lady Gregory’s and William Butler Yeats’ manifesto was “to bring upon the stage the deeper emotions of Ireland”.

Abbey Theatre programme first production

In the Grania theatre programme note, written by Colm Tóibín, writer and Laureate for Irish Fiction 2022 - 2024, he comments that Lady Gregory was an accomplished writer and playwright in her own right, whose ability and talent was not initially recognised by W. B. Yeats.

Lady Gregory’s journeys around the west of Ireland in the 1890s motivated her to learn the Irish language, subsequently translating and publishing volumes of Irish folklore. She published the legend of Gráinne, Diarmuid Ua Duibhne and Fionn mac Cumhaill as part of Gods and Fighting Men (1903), which was the foundation for her 1912 play Grania.

Lady Augusta Gregory’s twelve sonnets were published, with her permission and without her name attached, as A Woman’s Sonnets by her lover, Wilfred Blunt, six weeks before her husband’s death. The sonnets are about a married woman, who is having a secret affair.

Grania- directed by Caitríona McLaughlin:

Grania is a tragedy surrounding a love triangle, involving love, lust, power and desire. Male domination and female emancipation.

Caitríona McLaughlin Photo Rich Gilligan RTE

Caitríona McLaughlin, artistic director of the Abbey Theatre, which is the National Theatre of Ireland, directs Grania, and in the theatre programme note says:

It is alarmingly frank about the sexual dynamic that plays out inside a love triangle, where a woman is side-lined by the passion between men…

…I was inspired by Cathy Leeney’s paper The New Woman in a New Ireland?: Grania After Naturalism, and the parallels she draws between Gregory’s vision of Grania as representative of a new Ireland, that steps out from the constraints of its mythic past into an unknowable future, and the chilling door slam of Ibsen’s, Nora Helmer, another sound that continues to reverberate down the decades across Europe.

Those two sounds, the arrested laughter and the door slam, go beyond speech but speak volumes. They are sounds of resistance and renewal, of wilful, sexually awakened, powerful women taking control of their destinies.

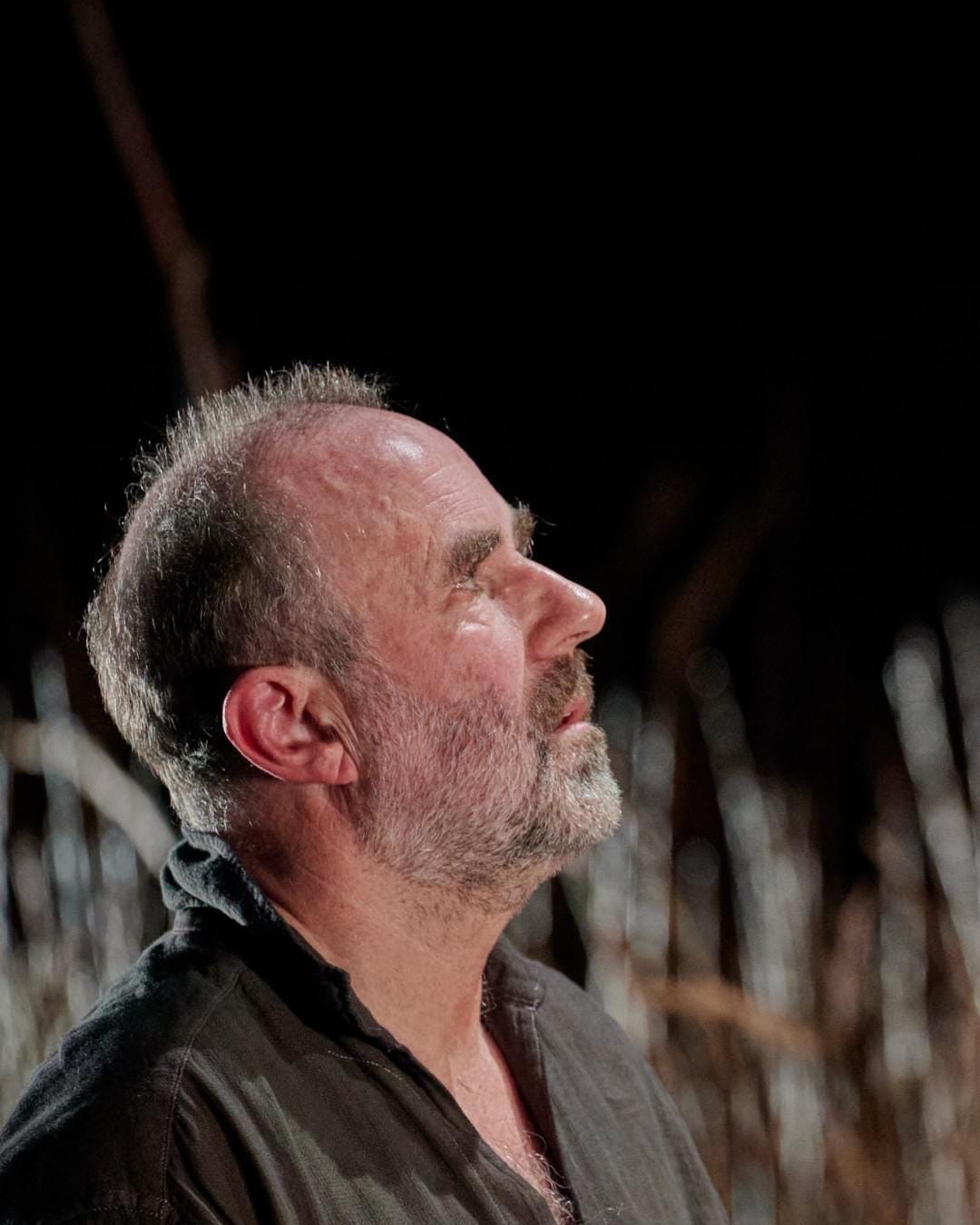

There are three main characters in this doomed love triangle. Finn, an ageing, legendary Irish warrior/ hunter and leader of the Fianna, is played by Lorcan Cranitch (The Crown series 6; Sharon Horgan’s Bad Sisters series 2; Lakelands with Eanna Hardwicke and Bloodlands with James Nesbitt).

Finn Photo Ros Kavanagh The Abbey Theatre

Grania, the king of Ireland’s daughter and betrothed to Finn, is played by Ella Lily Hyland (Amazon’s Fifteen Love with Aidan Turner).

Grania Photo Ros Kavanagh The Abbey Theatre

and Diarmuid, Finn’s faithful young warrior, is played by Niall Wright (Hope Street BBC).

Diarmuid Photo Ros Kavanagh The Abbey Theatre

There is a short musical prelude at the start of Act 1, where we have a modern day pop up tent and two homeless people - a couple I think.

Photo Ros Kavanagh The Abbey Theatre

The couple (Sean Boylan and Laura Sheeran), dressed in puffa jackets, hats and scarves, sing several of Lady Gregory’s twelve sonnets in beautiful harmony - at the beginning of the play and again between Acts 1, 2 and 3.

If the past year were offered to me again,

And the choice of good and ill before me set

Would I accept the pleasure with the pain

Or dare to wish that we had never met?

Ah! Could I bear those happy hours to miss

When love began, unthought of and unspoke -

That summer day when by a sudden kiss

We knew each other’s secret and awoke?

Carl Kennedy composed the music to these sonnets. But it is sometimes hard to decipher some of the words, and this, I feel, reduces the pace of the play.

To me, this attempt to place the age-old Irish experience of displacement and exile against the current immigration crisis and in particular to the many pop up tents that sprung up around government buildings on Mount Street and the Grand Canal in Dublin in summer 2024, feels somewhat clumsy and shoe-horned.

Photo Irish Times Sam Boal/Collins

I would question whether this modern day immigration add-on contributes any real value to the tragic love story that is Diarmuid and Grania.

The beautiful, evocative set, contains several levels and layers of fields of grain, reeds and bull rushes and a clever submerged pool, designed by Colin Richmond, and bathed in Sinéad Wallace’s golden lighting.

In the opening scene of Act 1, Grania arrives at Finn’s home, the day before their arranged wedding. They discuss love and marriage.

FINN: They told me you could have made great marriages, not coming to me?

GRANIA: My father was for the King of Foreign, but I said I would take my own road.

This initial somewhat slow, occasionally disjointed conversation demonstrates both Finn’s potential for jealousy and Grania’s independent spirit.

Grania and Finn Photo Ros Kavanagh The Abbey Theatre

In Finn and Grania’s discussion of love and marriage, three central themes in the play emerge - love, discontent (in love and marriage) and jealousy:

GRANIA: I asked the old people what love was, and they gave me no good news of it at all. Three sharp blasts of the wind they said it was, a white blast of delight and a grey blast of discontent and a third blast of jealousy that is red.

FINN: That red blast is the wickedness of the three.

GRANIA: I would never think jealousy to be so bad a smart.

FINN: It is a bad thing for whoever knows it. If love is to lie down on a bed of stinging nettles, jealousy is to waken upon a wasp’s nest.

GRANIA: But the old people say more again about love. They say there is no good thing to be gained without hardship and pain, such as a child to be born, or a long day’s battle won. And I think it might be a pleasing thing to have a lover that would go through fire for your sake.

The pacing of the play at times feels uneven and laboured and there are many long sentences.

In Act I, just before Diarmuid’s entrance on stage, as the audience, we are introduced to Lady Gregory’s use of audible offstage laughter (the Fianna perhaps) when Grania says to Finn:

It is a good thing surely, that I will never know an unhappy, unquiet love, but only love for you that will be by my side forever. (A loud peal of laughter is heard outside.) What is that laughter? There is in it some mocking sound.

Throughout the play, Gregory uses offstage laughter to draw our attention to key moments within the story. It is as if the men of the Fianna are mocking Grania. In my mind, the laughter sounded almost like wild geese. Is that significant?

We will return to this use of offstage mocking laughter in the closing scene of the final third act of the play.

Finn describes Diarmuid to Grania as:

the branch and the blossom of our young men.

Later, Diarmuid describing his friendship with Finn, states:

I am your son and your servant always, and your friend.

Diarmuid and Finn Photo Ros Kavanagh The Abbey Theatre

It is clear to the audience, when Diarmuid arrives and is introduced to Grania by Finn, that Diarmuid and Grania know each other already. They met briefly at Tara in the past, when she was a young girl and he saved her little dog. That is when Grania fell in love with Diarmuid.

Later that night, in the dark, Grania accidentally proclaims her love for Diarmuid, believing that she is speaking to him, when in fact it is Finn.

When Finn realises that Grania and Diarmuid love each other, he becomes angry with both of them, accusing Diarmuid of a lack of trust. Diarmuid goes to protect Grania from Finn’s wrath and attempts to assure Finn of his loyalty:

DIARMUID: I will not forsake her, but I will keep my faith with you. I give my word that if I bring her out of this, it is as your queen I will bring her and show respect for her, till such time as your anger will have cooled and that you will let her go her own road. It is not as a wife I will bring her, but I will keep my word to you, Finn.

Finn does not believe Diarmuid and claims that the eventual hag with matted hair (ie Grania) will cause him to break his oath before the next full moon. Diarmuid responds by lifting a round loaf of white bread and promises that he will send a full, clean, unbroken loaf to Finn every full moon as a sign that he has not broken his oath. Diarmuid makes it clear to Grania that he will not have sexual relations with her nor marry her.

At the end of Act 1, as Diarmuid and Grania leave, Finn threatens that no matter where they go, he will hunt them down and no one will give Diarmuid and Grania shelter and safety.

Photo Ros Kavanagh The Abbey Theatre

Photo Ros Kavanagh The Abbey Theatre

Act 2 commences seven years later. The passage of time and the turning of the seasons are communicated quite beautifully by the use of visual and acoustic heavy rain, golden and red falling autumnal leaves and soft snow falling in cyclical repetition. I confess, I empathise with the poor Abbey Theatre employees, who have to clean the stage every evening at the end of the performance.

Diarmuid and Grania:: Seven long years in exile, on the run from Finn. Photo Ros Kavanagh The Abbey Theatre

Diarmuid and Grania are naked. Finn stands sideways to the left, spearing fish in the water. Grania is centre stage, bathing in the submerged water, amongst the rushes.

Grania Photo Ros Kavanagh The Abbey Theatre

Her body language communicates her sensuality, wilfulness and sexual yearning for Diarmuid, who so far has kept his oath to Finn, to resist having a physical relationship with Grania.

Again, I initially question the need for full nudity in the play. It certainly makes us sit up but is it just a gimmick? My godson and nephew, a deep thinker, feels it reminds him of Adam and Eve in the garden of Eden, where their nakedness symbolises their innocence and lack of sin.

But then a few days later, listening to a 20 minute radio interview about Grania with Caitríona McLaughlin and Lorcan Cranitch, I remember. In secondary school in our final year before our Leaving Certificate Examinations, as students, we learnt about the legend of Diarmuid and Gráinne in Irish Language and Literature. There was a lesson with our formidable Irish teacher Miss Whelan, where Grania accidentally walks into a puddle, when on the run with Diarmuid, and water splashes up onto her inner leg. At this stage, Diarmuid and Gráinne have not consummated their relationship and Gráinne taunts Diarmuid by telling him that the little drop of water is braver than he, the finest Fianna warrior, because Finn will not touch her intimately. At the time, we all giggled in class with embarrassment.

So perhaps, Caitríona McLaughlin’s use of a naked Grania bathing in a submerged pool of water in the wild is actually appropriate.

Diarmuid and Grania Photo Ros Kavanagh The Abbey Theatre

Some action occurs offstage in the performance and is reported. This slows down the pace. A fight with the rival King of Foreign, who finds Grania hiding by the pool and lifts her up, is the spark that prompts Diarmuid to finally make love to Grania.

Diarmuid and Grania Photo Ros Kavanagh The Abbey Theatre

Grania reminds Diarmuid that it was actually jealousy and rage with the King of Foreign, that prompted him to kiss her and consummate their relationship, after a long seven year period of celibacy, on the run.

Grania is discontent with living in exile, on the run from Finn, who has never tired of hunting the couple down. She misses home comforts, social company and the respect of their peoples, now that they are married. Grania would like to return to her father’s home at Tara, but Diarmuid says it would not be safe. He wonders whether they could find another permanent home, out across the sea, beyond the craggy Burren and the Aran islands.

Grania feels that life is passing her by and that she is aging:

And I will go no more wearing out my time in lonely places, where the martens and hares and badgers run from my path, but it is to thronged places I will go, where it is not through the eyes of wild, startled beasts you will be looking at me, but through the eyes of kings’ sons that will be saying: “It is no wonder Diarmuid to have gone through his crosses for such a wife!” And I will overhear their sweethearts saying “I would give the riches of the world, Diarmuid to be my own comrade.” And our love will be kept kindled forever, that would be spent and consumed in desolate places, like the rushlight in a cabin by the bog.

They bicker and Grania taunts Diarmuid by referring to the King of Foreign putting his arms around her and kissing her, when he found her by the pool.

Finn arrives, disguised as a beggar, wearing a mask. Diarmuid and Grania do not recognise him. The beggar (Finn) says he has been sent by his master to obtain a message from Diarmuid, since this lunar month, no round, unbroken loaf of bread was sent to Finn, as a message from Diarmuid that he has kept his oath and not had sexual relations with Grania.

Diarmuid is hesitant and does not want to communicate to Finn that he has broken his vow; consummating his relationship with Grania and is now married. Finn says:

It is not fear that is on me, it is shame. Shame because Finn thought me a man would hold to my word, and I have not held to it. I am as if torn and broken with the thought and memory of Finn.

And that is the crux of the problem Grania has with Diarmuid and Finn’s friendship. That loyalty is an obstacle and a barrier between the love that Diarmuid and Grania share for each other.

Finn and Grania Photo Ros Kavanagh The Abbey Theatre

Grania wilfully crumbles the round loaf of bread into the beggar’s hands and tells the beggar to take that message back to Finn. Could the image and act of breaking the round, white bread loaf be a reference to the breaking of bread in the Christian Eucharist?

Finn, in disguise, taunts Diarmuid that rumour has it that the King of Foreign had his arms around Grania’s neck and that he still lives. Diarmuid must be a weak man if he hasn’t taken revenge against the King of Foreign. Diarmuid makes to gather his sword and his spear, but Grania stops him. She pleads with Diarmuid not to leave her alone. But Finn continues to jeer Diarmuid, sneering that he is just a housekeeper, plumping pillows with feathers, and not a warrior at all, who would fight and kill the King of Foreign, to protect his wife’s honour. Act 2 finishes with Diarmuid rushing away to seek revenge on the King of Foreign.

The final Act 3 opens several hours later on the same day. Grania is alone, when Finn arrives with the sound of horns and music, dressed as if for war, with a banner in his hand. Grania is startled that Finn has finally found her.

Finn and Grania Photo Ros Kavanagh The Abbey Theatre

Finn says he will not take Grania with him, unless it were of her own free will. Grania retorts:

That will be when the rivers run backwards.

Finn responds that today may be that day when the gravitational pull of the moon causes the tide to change. He takes out the golden crown from beneath his cloak, and lifts it up for Grania to see.

Grania makes it clear that she will never forgive Finn for being a “hedge” and a “shadow” that came between herself and Diarmuid in their long, seven year’s exile together.

Finn shares with Grania that he was actually disguised as the beggar - so that he could deliberately rile and stir up Diarmuid. His vengeful strategy to stimulate Diarmuid to fight the King of Foreign was successful. Grania is enraged.

Diarmuid arrives back, bloody and badly wounded, carried in by two young men. Both Finn and Grania believe he is dead. However, Diarmuid temporarily regains consciousness on his deathbed and it is here that he delivers the final humiliation to Grania. He ignores her, forgets her completely, remembering only that some resentment had come between himself and Finn that he thinks may have involved a hound. At the moment of Diarmuid’s death, Grania and Finn vie for his love, engaging in a bitterly emotional tug of war for his affections.

Grania Photo Ros Kavanagh The Abbey Theatre

Grania comes to understand that she has been playing second fiddle to the men’s love for each other all this time. She is determined to leave as Finn’s wife and queen.

It is not with Diarmuid I am going out.

Finn urges Grania to:

Wait till the months of mourning are at an end and till your big passion is cold.

But Grania refuses to take on this expected, traditional role of the keening widow. She fixes and fastens her hair, as if making ready to leave on a journey. Seeing Diarmuid banish her “from his thoughts” at the moment of his death, Grania asks herself:

Why would I fret after him that so soon forgot his wife, and left her in a wretched way?

Grania takes a stand to defend herself, reclaiming her golden crown and clamping it upon her own head.

Grania Photo Ros Kavanagh The Abbey Theatre

In this single act, a steely, defiant Grania silences her detractors and determines her own future. She herself opens the door to leave. The candle is blown out and the offstage mocking laughter of the Fianna stops abruptly. In this moment, Grania now has autonomy and will no longer accept male domination, similar to the dawning of a new Ireland, that will no longer accept imperialist rule.

Caitríona McLaughlin says:

Technically, it is a coup de théâtre that illustrates Gregory's total command of the form: the laughter that chokes on the threshold of revelation. That arrested sound tells us, resolutely, that Grania has taken control and has crowned herself, and in the darkness that follows she steps into her future. It is an instant when the mythic is transcended and finds resonance in our own present tense: that sudden halt when a woman is suddenly heard and seen and respected on her own terms.

Thank You for reading Free-Styling @60.

Clicking the heart, sharing and/or commenting below all help other people find my work.

If you have enjoyed my writing and aren’t already a subscriber, please do sign up here - it’s free.

Super review Caroline .... really added to my memories of the actual play xx

Brilliantly constructed article and very well written

A thoroughly enjoyable and very interesting read