Christmas Reindeer and Memories of the Arctic Circle

Reindeer and other deer at Wildwood Trust Kent; the Giant Irish Deer; A Norwegian journey north into the Arctic Circle; two favourite childhood Christmas songs and a recipe for Rudolf Shepherd’s Pie.

Introduction:

Photo author: Theodore Waddell painting, Denver Art Museum, August 2014

In my last article, I shared that our young, adopted son’s first school Nativity play involved him dressing up as a cowboy and that the primary school children sang a haunting song about Bison on the great American plains.

This week, I had the privilege of working with the larger hoofstock animals at Wildwood Trust Kent. This included bison, elks, fallow deer, red deer and, of course, the perennial Christmas favourite - the reindeer.

So today, I am going to explain what I have learnt about these truly majestic animals. I would also like to share with you some personal memories of our trip to Norway and the Arctic Circle earlier this year, where we met reindeer, learnt about the Sámi people and their unique culture and witnessed the mesmerising Northern Lights. And I will finish with a delicious and warming recipe for a festive venison shepherd’s pie.

European Bison (Bison Bonasus):

Photos: author

There are two living species of Bison - the European and the American Bison. The bison is the heaviest wild land animal in Europe, weighing between 400-1,000kg and standing up to 2 metres tall. In the wild, bison have a lifespan of approximately 24 years.

Bison belong to the bovine family (which includes cattle) and both males and females have horns. They have a distinctive, muscular humped shoulder and short legs.

Historically, the bison could be found throughout western, central and south eastern Europe. During the Middle Ages, bison were hunted and killed for their meat, hides and their horns - which were used for drinking. As a consequence, by the early twentieth century, bison had been hunted to extinction in Europe.

There were only 54 animals left in captivity. In 1929, the first successful reintroduction of Bison from zoos took place in the Białowieża Forest in Poland. European Bison have been reintroduced into the wild across Europe - including Poland, Latvia, Spain, Denmark and the Netherlands.

Fortunately, due to conservation work and reintroductions, in 1996, the International Union for Conservation of Nature was able to reclassify the European bison as endangered, rather than extinct. They are currently classified as Near Threatened (NT). Today, total worldwide population is approximately 9,000 individuals.

The bison’s usual habitat is mixed forest and grassland. Bison are diurnal herd animals. Herds can be mixed or bachelor herds. Mixed herds tend to have more individuals (typically 13 animals) and consists of adult females, calves up to 2-3 years and young adult bulls.

The main threat to bison is habitat loss and fragmentation due to agriculture and tree logging.

In 2019, Wildwood Trust and Kent Wildlife Trust launched a rewilding project, ‘Blean bison' in Blean woods, Kent. The project promotes complex and resilient habitats. In Britain, the lack of woodland management is one of the eight biggest drivers of species decline. Whilst European bison were never native to Britain, Steppe Bison and other wild grazing animals were. European bison offer us a chance at recreating those grazing behaviours that once existed. Despite their size, bison are peaceful animals whose ability to fell trees by rubbing up against them and eating the bark, gives space for other plants and animals to thrive.

Gestation period is 264 days and a cow usually gives birth to one calf. In winter 2023, the first bison was conceived and born in Britain for thousands of years, in Blean woods.

This week, I fed and worked with two Bison - Fury and Haze. Bison are browsers, feeding mainly on leaves, bark, shrubs and tree shoots. Fury and Haze enjoyed eating browser pellets, deer rolls and vegetables (cabbage, kale and carrots).

I observed a training session with the bison and senior keepers - the purpose was to acclimatise the bison to being touched/ given medicine. Operant conditioning is the basis of animal training. It is a type of learning in which an animal learns (or, is conditioned) from its behaviours as it acts (operates) on the environment. In operant conditioning, the likelihood of a behaviour is increased or decreased by the consequences that follow.

The three keepers were teaching the bison three commands Turn; Touch Good and In (the bison presses his side into the small wooden brush to get more food), using sound and visual commands, and subsequent food rewards.

Two keepers were positioned at either end of the bison. One rewarded food (kale and pellets), when the bison turned and changed direction on command. The second person held the hand brush (simulator for hand held syringe). The third keeper gave the verbal commands and the visual arm signpost directions. It was fascinating to watch.

Eurasian Elk (Alces alces):

This is Jurgen. He was born in May 2022. His female companion at Wildwood Trust Kent is Caramel, born in May 2012. Caramel is friendly and chatty. Jurgen is more aloof but will observe you very carefully if you approach his territory.

Photo: Dave Butcher Wildwood Trust Kent

The Eurasian elk, commonly called a moose, is the largest member of the deer family, and was commonly found in Britain and Ireland, until 3000 years ago. They became extinct due to climate change and hunting. There is some evidence that they may have survived in Scotland until around 900 A.D.

Elks have a heavy body, humped shoulders, long legs and a short tail. They have a distinctive skin fold under their chin, called a dewlap or bell and a large, overhanging nose or proboscis. Elks have an exceptional sense of smell.

The male elk’s palmate antlers (like an open hand) can reach up to 2 metres across - the largest antlers of any non-extinct deer species. The antlers are covered in skin and a soft, short fur called velvet. The male antlers grow and are then shed annually. The female elk does not have antlers.

Elks weigh between 200 - 700 kg; have a body length between 240 - 310 cm; are 140 - 230 cm high and have an average lifespan of 29 years.

Elks have two wide hooves on each foot, which splay - an advantage when walking on mud, snow and for swimming.

The elk is found in Northern America, Canada, Northern Europe, Russia and China. The elk’s preferred habitat is woodland, with swamps, lakes and wetlands, in cooler climates.

Elks are herbivores and browse on the non- grass understory of forests. They eat fruits and deciduous and coniferous trees.

At Wildwood Trust Kent, Jurgen and Caramel are fed three times per day, on a diet consisting of browser pellets and lucerne hay.

Elks can dive under water to approximately 6 metres deep and close their nares, to stop water entering their nose. Elks sometimes eat aquatic plants. They enjoy wading and swimming in water in the summer months, to cool down.

Elks are solitary and diurnal. A female elk will choose a mate with the largest antlers. Cows normally give birth to twins. Calves stay with their mother until they are approximately one year old.

Elks experience minimal threats in their existing range. However, they are sometimes hunted for meat and numbers are sometimes controlled as a pest of agriculture and forestry.

I have been told by experienced ranger staff at Wildwood Trust Kent, that the male Elk is potentially a more dangerous animal than the bear, if provoked. Magnificent, strong and very large.

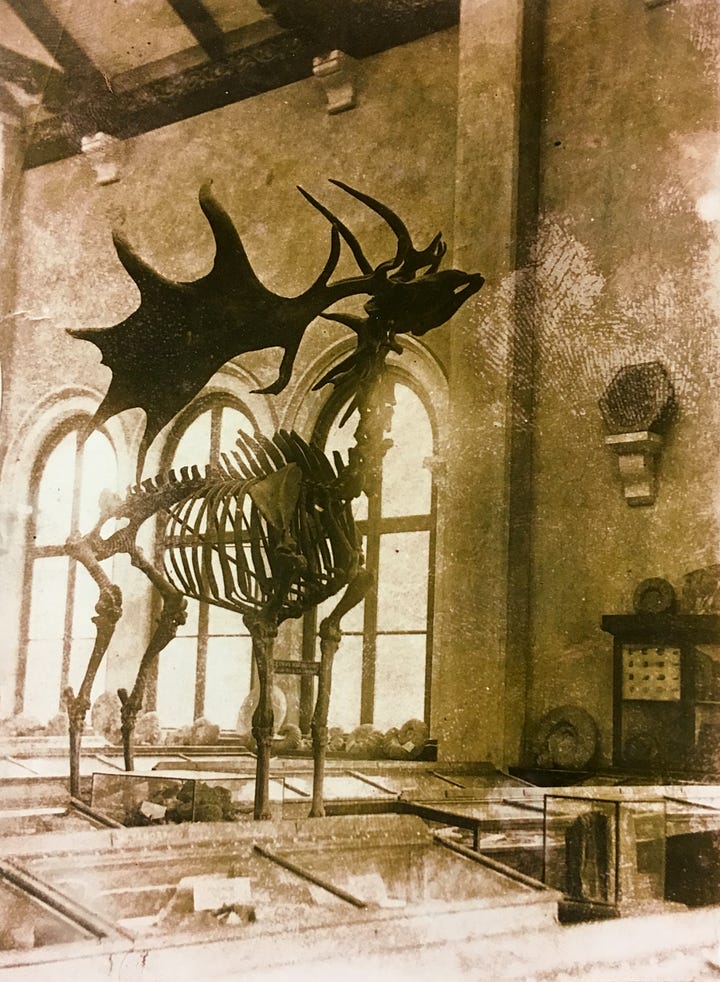

The Giant Irish Deer (Megaloceros giganteus):

If you have read my previous articles, for example:

You may be aware that I studied Natural Sciences for my undergraduate degree at Trinity College Dublin. Our father worked here, in the late 1970s, in the maintenance and electrical department. Our family pine kitchen table was repurposed and originally came from Trinity College (regrettably now gone; that kitchen table could tell a few family stories).

But I digress - for my undergraduate degree in Natural Sciences, I studied Geology, Physics and Mathematics. Our Geology lectures took place in the spectacular and sumptuous Museum Building, built between 1853-57, by Thomas Deane and Benjamin Woodward, using a large number of different rock types. The external walls are built from Calp Limestone and faced with Ballyknockan granite. The quoins, columns and capitals, as well as the string course that can be seen halfway up the building, are made from Portland stone, Dorset. The tympanum over the large wooden entrance door to the building, that bears the College crest, is made of Caen stone from Normandy, France. The exterior build amounted to just under half the cost for the entire building.

Inside, the main entrance hall houses large pillars, balustrades and bannisters constructed from a variety of Irish marbles and Cornish serpentine, while the domed roof is made of blue, red and yellow enamelled bricks.

Patrick Wyse Jackson, now Associate Professor of Geology, and then a Geology student in the year above me at Trinity College, says:

Built at the start of the golden age of Ireland’s decorative stone industry, Trinity’s Museum Building set out to showcase the extraordinary potential of Irish decorative stone. Featuring stone from right across the country the building is an Irish geology lesson in itself — in a few strides a visitor can encounter stone from the length and breadth of the country. The dominant use of Irish stone and the depiction of native Irish plants and animals in the building’s carvings were in keeping with a post-famine drive to promote and exploit Ireland’s natural resources through various Great Exhibitions and the newly launched ordnance and geological surveys.

It is an utterly resplendent and romantic building. I can vividly remember, as a young, inexperienced undergraduate in the early 1980s, sliding down those bannisters, polishing the marble with my then petite derrière, after one too many glasses of red wine, at a Geology department Christmas party. Then, whilst cycling on a path towards Pearce Street train station, via the Pavilion Bar, I crashed into two bollards linked with chains, flying upwards and over. I survived - but it was a salutary lesson. I am still digressing…

Anyway, back to the point (the Deer). In the Geology department Museum Building entrance hall, there is an imposing skeleton of the iconic Ice Age Pleistocene mammal, the Giant Irish Deer (Megaloceros giganteus).

Originally, it was thought that this giant mammal, now extinct due to climate change, was related to the elk. However, more recent genetic/DNA studies now indicate that Megaloceros giganteus is more closely related to the fallow deer, despite its very large size. These noble animals were as big as a horse and had the largest antlers ever seen on a deer, at almost four metres.

Check out this YouTube video from the National Museum of Ireland (2022). The very interesting and informative talk about the Giant Irish Deer Megaloceros giganteus by Nigel Monaghan is approximately 20 minutes long. Feel free to skip the introduction and the subsequent Q & A.

YouTube: National Museum of Ireland 2022

Fallow Deer (Dama dama):

Photo: Wildwood Trust Kent

Fallow deer were first introduced to Britain by the Romans. Later, after the Battle of Hastings in 1066, William the Conqueror and the Normans brought fallow deer from the Mediterranean and Asia. The Fallow deer is now Britain’s most common deer species.

The fallow deer weigh between 50 - 80 kg; are up to 110 cm at shoulder height and have an average lifespan of 16 years.

Fallow deer are usually a light brown or tan colour with white spots. However, three genetic colour variations exist - “menil” (similar to common fallow deer but much paler), “melanistic” (black to very dark brown with faint spots), and “white” (sandy to completely white with no spots).

The fallow deer can run very fast (up to 36 miles per hour); they can jump 1.75 m vertically and 5 m horizontally.

The male fallow deer, the buck, has flat palmate antlers, with a protective organic velvet covering. These antlers are shed every spring, and regrow during the summer. The female fallow deer does not have antlers.

The female fallow deer, the doe, can give birth to one fawn per year.

Fallow deer live in deciduous woodland, shrub land, grassland, pasture and agricultural areas.

Fallow deer herds are small, normally numbering between 10 - 50 animals. Fallow deer shelter in woodlands by day and emerge to feed in open areas during the night, but are active throughout any 24 hour period.

Grass is approximately 60% of their diet. Fallow deer will eat a variety of plant material such as herbs, acorns, and fruits.

At Wildwood Trust Kent, fallow deer are fed three times per day - browser pellets in the morning and hay at lunchtime and in the evening.

There are no major threats to the fallow deer in Europe.

Red Deer (Cervus elaphus):

The male red deer is called a stag or a hart and the female red deer is called a hind.

Photo: Male Red Deer - the stag, Wildwood Trust Kent

Photo: Two female Red Deer - hinds, Wildwood Trust Kent

The Red stag can weigh between 160 - 240 kg, with a height of 1.4 m. The Red hind weighs between 120 - 170 kg, with an average height of 1.2 m. Typical lifespan in the wild is 13 years. Red deer have a plain reddish-brown fur, with no spots or patterns. They do have a distinctive pale patch on their rump.

The red deer stag has spectacular antlers, with three main branches. Female red deer do not have antlers.

Red deer have an impressive range of vocalisations.

Some common Red deer sounds include:

Roaring: During the rutting season, stags will roar loudly to attract females and challenge other stags. This sound is deep, resonant, and can be heard from a distance.

Grunting: Both stags and hinds may grunt as a form of communication or alarm. This sound is shorter and less intense than a roar.

Barking: A rapid series of short barks can be used as a warning or threat display.

Snorting: A snorting sound is often made when a deer is startled or feels threatened.

The best time to see red deer is during the autumn rut (September to November), when stags are most active and can often be seen battling for dominance. The purpose of a stag’s autumnal rutting is to guard his hinds, and when posturing and roaring are insufficient, the stag will fight.

The red deer is a grazer and like all deer, is a ruminant with a four chambered stomach. In the wild, their preferred diet is predominantly different grasses and rushes. During the winter, when food can be limited, tree shoots, shrubs (such as heather) and woody browse are additionally consumed.

At Wildwood Trust Kent, red deer are fed three times per day - browser pellets in the morning and hay at lunchtime and again in early evening.

The red deer’s range is patchy and extends from Europe, into North African, the Caucasus Mountains region, Anatolia, Iran, the Middle East and parts of western Asia. Some regional populations have become almost extinct and then subsequently been reintroduced (such as those in Ireland, Greece and Portugal).

In Britain, the largest numbers of red deer occur in Scotland, although there are some small populations in the Lake District in Cumbria, East Anglia, Exmoor, the New Forest in Hampshire, Margan Country Park and the Brecon Beacons National Park in Wales, and of course Richmond Park in London.

In Ireland, Red deer are the largest deer species and wild land mammal. Research has shown that they have had a continuous localised presence in Ireland since Neolithic times over the past 5,000 years. As a result of deforestation, over hunting and the Great Famine (1845 – 1847), many localised populations around Ireland became locally extinct. By the middle of the 19th century the last home of the Red deer was in the woodlands and mountains around Killarney, where their preservation was due to the strict protection of the two large estates of the Herberts of Muckross and the Brownes, Earl of Kenmare. The current population in Kerry, is the only red deer population in Ireland that can claim the long ancestry – direct descendants of a 5,000 year old introduction of native Scottish red deer from Britain. All other populations were introduced to Ireland from the 19th century onwards.

The red deer’s habitat includes mixed, broad leafed and coniferous woodlands, as well as open areas such as moors, grasslands, meadows and open mountainous regions.

The main threat to the Red Deer is hybridisation with introduced species (sika deer). Deer culling is also a major limiting factor for deer numbers in Britain, although current rates in the Scottish Highlands are shown not to stop population increases.

Reindeer (Rangifer tarandus):

I can remember as children, when our parents were out at Christmas time, we would turn off the house lights, with the exception of the Christmas tree lights. Then, we would play Gene Autry’s Christmas Cracker vinyl LP record on repeat, dancing around the sitting room, giddy with excitement, in the days leading up to Christmas Eve, when Santa Claus would arrive with presents.

Photo author: Gene Autry’s Christmas Cracker vinyl LP 1966

Rudolf, the Red-Nosed Reindeer was our favourite song.

YouTube: Gene Autry

I purchased a second hand copy of this vinyl LP a few years ago, along with digitally remastered CDs of the album for each of my siblings.

Gene Autry, nicknamed “the Singing Cowboy”, was an American actor, musician, singer, composer and rodeo performer from Texas. What is it about cowboys and Christmas?

Photo: Gene Autry 1940s Amazon

Gene Autry’s Nine Little Reindeer was another favourite Christmas song of ours as children, making us run and dance around the sitting room even faster:

YouTube: Gene Autry

The reindeer is known as the caribou in North America. Weight ranges from 120 - 180 kg. Compared to other deer types, reindeer have the largest antler size relative to their body size. In contrast to the elk, fallow deer and red deer, both male and female reindeer have antlers.

The reindeer’s fur colour varies between grey and dark brown - depending on the season, locality and the individual. There are two layers of fur. An inner, dense, fluffy layer is surrounded by a hollow, longer overcoat. The trapped pockets of air act as insulation, reducing heat loss.

The reindeer’s hooves are large, splayed and crescent shaped. The large surface area reduces the pressure, which prevents the reindeer’s hooves from sinking into deep snow.

Reindeer are found in the most northerly part of the northern hemisphere around the Arctic (Norway, Finland, Russia, Canada), but this range has expanded to Iceland and Atlantic islands due to the introduction of domesticated reindeer. The reindeer’s habitat in the wild, consists of boreal forests, arctic polar deserts, tundra, coastal plains and mountain ranges.

Historically, reindeer were once found much further south than their current geographical range (even down as far as Spain in southern Europe). Reindeer became extinct in Scotland, but were reintroduced to the Cairngorm National park in 1952. The total number living wild in Scotland is approximately 150.

Reindeer are herbivores, eating seasonal herbs, sedges, grasses, mosses, fungi and the shoots and leaves of shrubs and trees, especially willow and birch. They select plants that are flowering or have newly unfolded leaves in order to maximise nutritional value in a barren landscape.

Reindeer is the only known large mammal able to digest lichen (also known as reindeer moss), a fungi-algi symbiote, due to specialised bacteria in their digestive tract. The reindeer scrape the snow away with their hooves to get the lichen. Reindeer have an excellent sense of smell, which they use to find food hidden under snow, locate danger, and recognise direction. Reindeer mainly travel into the wind so that they can pick up scents.

In the wild, reindeer live in large migratory herds of approximately a few hundred, but can form super herds of 50,000 to 500,000 during spring migrations. Migrations are dictated by food sources, normally travelling 19 - 55km each day.

Reindeer are the only deer species to be widely domesticated. They were first domesticated by Arctic peoples around 3,000 years ago. They are used as draught animals to pull heavy loads and farmed for their milk, meat, and hides.

There are currently two reindeer, Mrs May and Willow, at Wildwood Trust Kent. Similar to other deer species, the reindeer is a ruminant with a four chambered stomach. At Wildwood, the reindeer are fed a combination of oats, barley, browser pellets and sugar beet, three times per day. The reindeer eat very politely from your hand. As with most wild animals, checking and removing faeces daily, is a good indicator of digestive health. Reindeer faeces should be very small (rabbit sized) and separate, not clumped together.

Photos: author

Reindeer herds can be very vocal, communicating with a series of snorts, grunts, growls and hoarse calls. Due to living inside the Arctic Circle, where day and night length can differ significantly from much southerly latitudes, reindeer have lost their circadian rhythm.

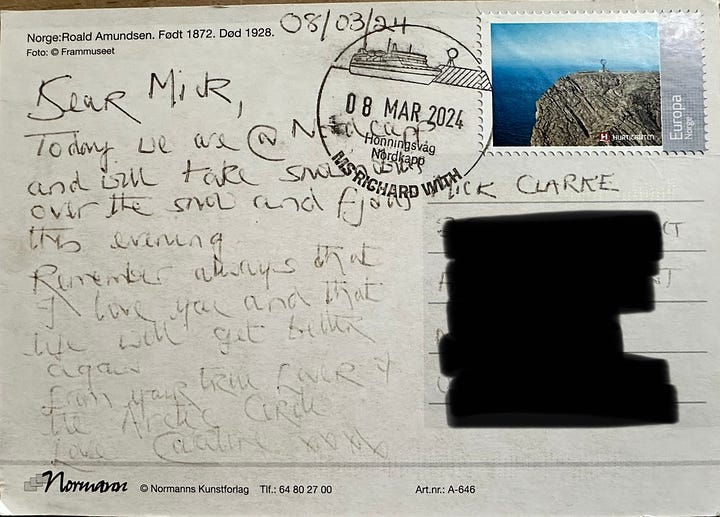

Our Norwegian Arctic Circle voyage, Reindeer, the Sámi Herders and the Northern Lights:

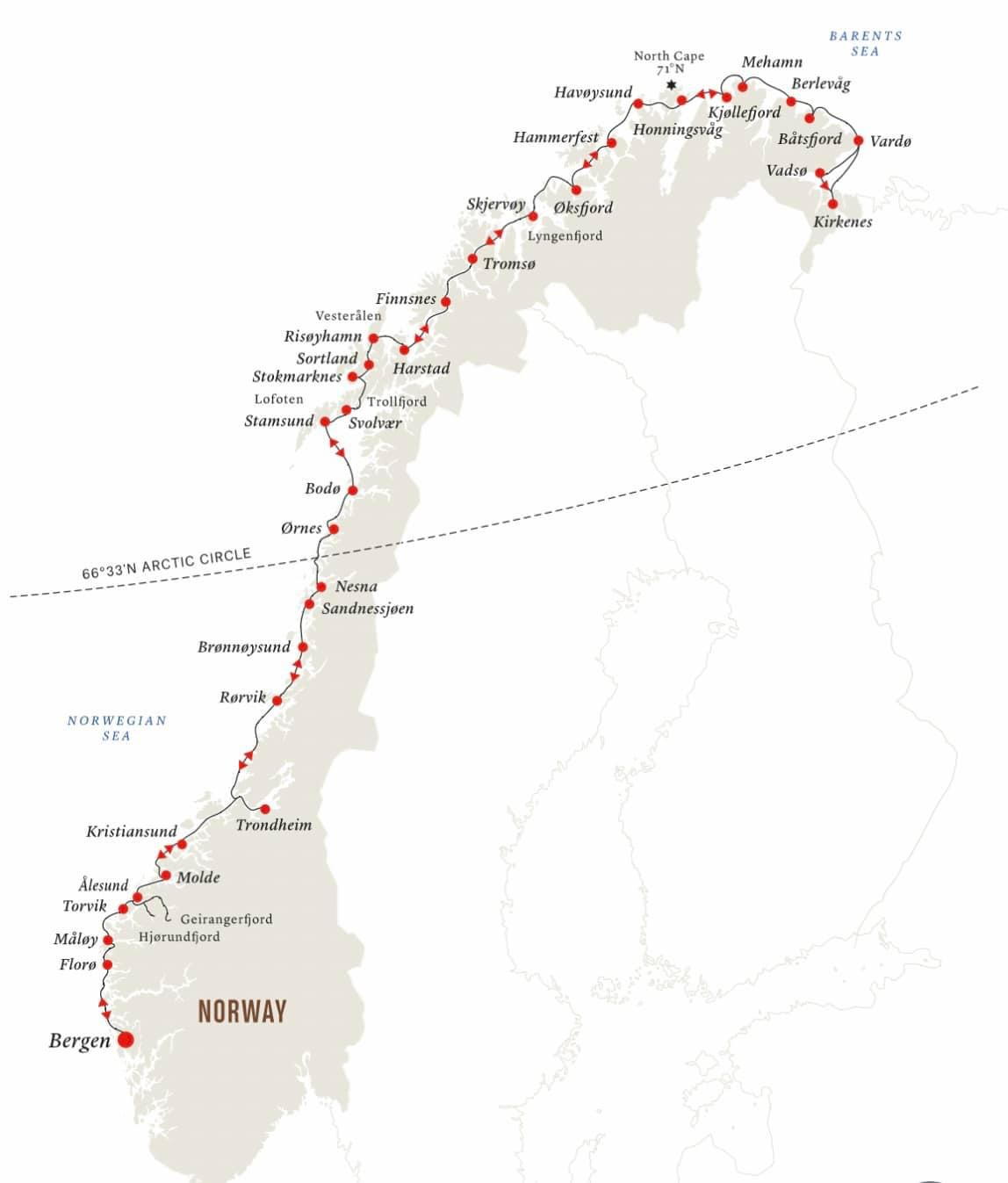

We were blessed to be able to visit Norway and the Arctic Circle in March 2024, travelling on the coastal Hurtigruten working postal ship MS Richard. We travelled from Bergen in the south, right up to Kirkenes in the north, close to the Russian border.

Map: Hurtigruten

The scenery, the skies and the pure Arctic air were both dazzling and divine; the wildlife was extraordinary and the Northern Lights took my breath away.

Photo: author

Photo: author

Photo compilation author Aurora Borealis 2 minute 30 seconds

We drove snow mobiles across the snow at midnight, near the Russian border. It was hair-raising, but afterwards I was glad I did it. We ate sparkling fresh Norwegian salmon, halibut, cod, scallops, crab and perky, spine-tingling pickled herring. I watched a sea eagle hunting, flying low overhead in a fjord.

Photo: author Sea eagle

We met a joyous team of seven, eager husky dogs who brought us on a sleigh ride across the snow and a frozen lake.

Listen to these beautiful, joyous husky dogs, who couldn’t wait for our sleigh ride journey to begin. Each one of them were absolute darlings:

Video: author, A magical Husky Sleigh Drive in the Arctic Circle, near the Russian border, in the snow and out onto a frozen lake

We drank Aquavit, a distilled spirit made from potatoes or grain, flavoured with herbs and spices, at the Ice Hotel:

The Sámi reindeer herders, their culture and historic discrimination:

And then, of course, there were the Reindeer.

Photo: Hurtigruten, Reindeer and a Sámi herdsman

There are approximately 25,000 wild reindeer and more than 200,000 domesticated reindeer in Norway today.

The highest concentration of reindeer held as livestock is found on the Finnmark plateau in the far north of Norway.

Reindeer are particularly well adapted to the subarctic climate, in the cold and windy Norwegian steppes and mountains, with their insulating double layer of fur, which is almost completely waterproof.

The primary food source for this tundra hero is lichen, which is tossed up under the hooves of flocks of as many as 4000 reindeer.

Reindeer herds are reared by the Sámi people for food, pelts, tools and for pulling sleighs and wagons.

The Sámi are an indigenous people living in Europe's northernmost region. Renowned for herding reindeer, their distinctive duodji traditional handicrafts, and their affinity with nature, the Sámi are a people rich in culture and history.

Sápmi, as the Sámi call it, is their territory area that extends from the middle of Norway to the northwestern tip of Russia and includes northern Sweden and northern Finland. Historically, both the reindeer and the Sámi people, who herd them, have travelled freely over the countries we now know as Norway, Russia, and Finland. The reindeer graze freely but are sometimes herded for marking or transporting between grazing areas.

Life as a Sámi reindeer herder is nomadic, following the reindeer’s instinctive migrations, from the inland plains to the coast in April and back again in September. The reindeer and the Sámi herders travel several hundred kilometres between summer and winter pastures.

The Sámi population in Norway experienced a very difficult period of persecution, starting in the 1850s, continuing through the 1900s, and only stopping in the 1960s.

This indigenous group suffered from harsh repression, discrimination and tough “Norwegianisation". They were forbidden from speaking their own language and had to learn Norwegian under strict assimilation policies. Young Sámi children were taken away from their parents and forced to live in foster homes and state-run boarding schools in the 1900s. Native cultural beliefs were suppressed by Christian mission churches belonging to the Evangelical Lutheran and Catholic denominations. The Sámi were forced to give up their previous shamanistic rituals. Traditional practices such as ‘yoiking,’ a traditional call of the Sámis, were forbidden

These “Norwegianisation” policies finally came to an end in the 1960s, with laws formally repealed or replaced in 1963. The Sámi people received a formal apology from the Norwegian king, Olav, in 1989, during the inauguration of the new independently elected Sámi Parliament in Karasjok. The Norwegian parliament has a working relationship with the independent Sámi parliament.

Today, the Sámi have a university, as well as schools teaching the Sami language. The Education Act of 1969 gave Sámi students the right to compulsory and upper-secondary education in their own language, and policies have also sought to integrate the language in school curricula.

Today, the Sámi culture is experiencing a new revival and is flourishing on its own premises.

Here is a 2 minute 36 second clip of the reindeer and Sami herders from the BBC documentary, All Aboard! The Sleigh Ride, originally shown in December 2015. In this documentary film, with no voice-over commentary, following the path of an ancient postal route, a traditional reindeer sleigh is rigged with a fixed camera for a real-time journey across the frozen wilderness of the Norwegian Arctic.

If you have enjoyed the short video clip above, you can watch the full documentary film (1 hour 57 minutes) here on YouTube. This is slow television at its very best. Perfect to relax with a glass of something festive, after the hectic preparations in the lead up to Christmas Eve.

Venison - a sustainable meat:

Venison is a sustainable meat. It has twice as many nutrients as beef, the same fat content as chicken, and as many amino acids and vitamins as white fish.

The reindeer on our Hurtigruten voyage menu that we ate, came from the herding groups in Finnmark.

Check out Jp McMahon’s recent Substack article on venison as a sustainable food in Ireland.

Jp McMahon is a Galway based chef & food writer, who owns Michelin-starred Aniar and Cava Bodega restaurants in Galway city and leads Food on the Edge.

I have copies of his two excellent books An Irish Cookbook and An Irish Food Story, published this year.

I haven’t been lucky enough to visit Cava Bodega or Aniar yet - but maybe next summer, when I will hopefully be back home in the west of Ireland, visiting the Burren and my cousins in Galway.

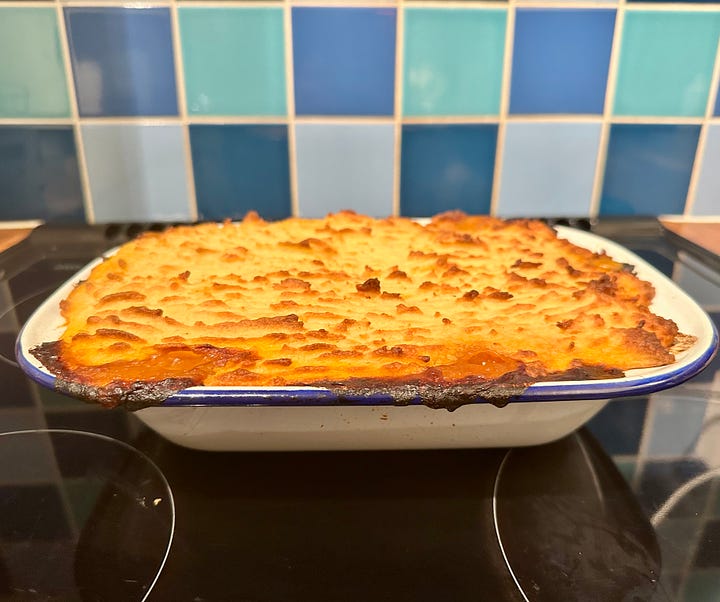

Nigella Lawson’s Rudolf Pie:

This recipe is from Nigella’s cookbook Feast (Food that Celebrates Life) 2004. It is my personal favourite Nigella book. This venison shepherd’s pie recipe makes a very tasty, comforting winter dish during the Christmas season, with the musky scent of porcini mushrooms. It’s great as a casual and cosy festive meal, that you can prepare in advance, to share around the table with good friends. I serve it with French petit pois peas.

You can buy seasonal and sustainable minced venison in a reputable independent, butchers or in larger branches of Waitrose, Sainsbury’s and Tesco supermarkets in Britain. At a butchers, it will be difficult to request your butcher to mince a small amount of venison, as the small amount of minced meat will become stuck at the back of the mincing equipment. Knowing this now, I usually use 1kg each of minced venison and pork, and then separate the final, cooked meat into smaller batches - one to cook in the oven and eat straight away, the rest to freeze for future meals. Do not make your parsnip and potato mash until you are ready to place it on top of your cooked meat mixture and immediately pop it in an hot oven.

Nigella adds a kitsch glacé cherry on top of the mash, in a nod to Rudolf the Red-Nosed Reindeer.

I finish this article with a narration of the 1823 poem ‘Twas the Night before Christmas’ by Michael Bublé.

Though its author is disputed, with the poem being attributed to both Clement Clarke Moore and Henry Livingston Jr. over the years, it was definitely first published on December 23, 1823 in the Troy Sentinel newspaper in upstate New York.

Wishing you, wherever you are, a relaxing and peaceful Christmas, filled with Love.

‘Twas the night before Christmas, when all thro' the house,

Not a creature was stirring, not even a mouse;

The stockings were hung by the chimney with care,

In hopes that St. Nicholas soon would be there;

The children were nestled all snug in their beds,

While visions of sugar plums danc'd in their heads,

And Mama in her 'kerchief, and I in my cap,

Had just settled our brains for a long winter's nap-

When out on the lawn there arose such a clatter,

I sprang from the bed to see what was the matter.

Away to the window I flew like a flash,

Tore open the shutters, and threw up the sash.

The moon on the breast of the new fallen snow,

Gave the lustre of mid-day to objects below;

When, what to my wondering eyes should appear,

But a miniature sleigh, and eight tiny rein-deer,

With a little old driver, so lively and quick,

I knew in a moment it must be St. Nick.

More rapid than eagles his coursers they came,

And he whistled, and shouted, and call'd them by name:

“Now! Dasher, now! Dancer, now! Prancer, and Vixen,

“On! Comet, on! Cupid, on! Dunder and Blixem;

“To the top of the porch! to the top of the wall!

“Now dash away! dash away! dash away all!"

As dry leaves before the wild hurricane fly,

When they meet with an obstacle, mount to the sky;

So up to the house-top the coursers they flew,

With the sleigh full of Toys - and St. Nicholas too:

And then in a twinkling, I heard on the roof

The prancing and pawing of each little hoof.

As I drew in my head, and was turning around,

Down the chimney St. Nicholas came with a bound:

He was dress'd all in fur, from his head to his foot,

And his clothes were all tarnish'd with ashes and soot;

A bundle of toys was flung on his back,

And he look'd like a peddler just opening his pack:

His eyes - how they twinkled! his dimples how merry,

His cheeks were like roses, his nose like a cherry;

His droll little mouth was drawn up like a bow,

And the beard of his chin was as white as the snow;

The stump of a pipe he held tight in his teeth,

And the smoke it encircled his head like a wreath.

He had a broad face, and a little round belly

That shook when he laugh'd, like a bowl full of jelly:

He was chubby and plump, a right jolly old elf,

And I laugh'd when I saw him in spite of myself;

A wink of his eye and a twist of his head

Soon gave me to know I had nothing to dread.

He spoke not a word, but went straight to his work,

And fill'd all the stockings; then turn'd with a jerk,

And laying his finger aside of his nose

And giving a nod, up the chimney he rose.

He sprung to his sleigh, to his team gave a whistle,

And away they all flew, like the down of a thistle:

But I heard him exclaim, ere he drove out of sight-

Happy Christmas to all, and to all a good night.

Painting: author, The Northern Lights, Oil pastels

I have just finished reading this wonderfully informative and very well researched article

I thoroughly enjoyed the article and this will not be the only time I will read the article

Perfect compliment to the season that will shortly be upon us

Very well done

I learned a lot reading this -- for example, that European bison almost became extinct, and that reindeer are often domesticated. This category of animal seems to be quite different in Northern American and Europe, so my French vocabulary for them is a bit of a mess.

And that trip! What an unforgettable experience.